© 2014 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/absolute-zero-is-0k/

Near the heart of Scotland lies a large morass known as Dullatur Bog. Water seeps from these moistened acres and coalesces into the headwaters of a river which meanders through the countryside for nearly 22 miles until its terminus in Glasgow. In the late 19th century this river adorned the landscape just outside of the laboratory of Sir William Thompson, renowned scientist and president of the Royal Society. The river must have made an impression on Thompson—when Queen Victoria granted him the title of Baron in 1892, he opted to adopt the river’s name as his own. Sir William Thompson was thenceforth known as Lord Kelvin.

Kelvin’s contributions to science were vast, but he is perhaps best known today for the temperature scale that bears his name. It is so named in honor of his discovery of the coldest possible temperature in our universe. Thompson had played a major role in developing the Laws of Thermodynamics, and in 1848 he used them to extrapolate that the coldest temperature any matter can become, regardless of the substance, is -273.15°C (-459.67°F). We now know this boundary as zero Kelvin.

Once this absolute zero temperature was decisively identified, prominent Victorian scientists commenced multiple independent efforts to build machines to explore this physical frontier. Their equipment was primitive, and the trappings were treacherous, but they pressed on nonetheless, dangers be damned. There was science to be done.

Prior to this 19th-century cold rush, most European scientists believed that coldness itself was an actual physical substance—made up of atoms of an airborne primordial gas. This explained why water expanded upon freezing—it was taking in a large amount of these cold particles. Physicist Robert Boyle dispelled this notion in 1665 by painstakingly weighing water before and after putting it outdoors on a freezing night, demonstrating that only its volume had changed, not its mass. This helped naturalists to start hypothesizing in the right direction, but in 1783, renowned French chemist Antoine de Lavoisier undid most of this progress by popularizing his own theory that heat is an invisible, weightless, self-repellent vapor called caloric, and that coldness is merely a depletion of the same. This “dark heat” theory was also wrong, but it modeled observations so well that it remained dominant for almost a century.

At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, newfangled steam machines began to chuff heat into work, and science into profits. Cracking the true nature of heat would lead to more efficient power plants, so the utmost intellectual and financial assets converged upon the problem. When centuries of “common sense” were finally set aside in favor of the scientific method, theorists and experimenters gradually ascertained that all molecules in nature are restless, agitated things that randomly wiggle and wobble, bumping into neighbors like billiard balls on an overcrowded table. The net effect of these molecular motions is what we observe as heat, and temperature is directly proportional to the speed of these movements. From this, Lord Kelvin inferred that if one were to reduce the heat in a substance sufficiently, one would reach a temperature where the molecules become entirely still—a minimum possible temperature. His calculations correctly indicated -273.15°C as this physical boundary.

This landmark discovery invited even more inquiry than it had quieted. Might it be possible to actually reach absolute zero? What would happen to molecules forced into such stillness? Would they disintegrate? Would they convert to a yet-to-be-observed phase of matter? Who goes there? What is the meaning of this?

One gentleman with the wherewithal to address these questions was Scottish scientist Sir James Dewar, an accomplished inventor and a professor at the Royal Institution in London. His history with cold was the stuff of origin stories—at the age of ten James Dewar was frolicking upon a frozen pond in Scotland when the ice cracked open beneath his feet. Young Dewar was swallowed into the dark, freezing water. His companions managed to extract him, soggy and shivering, but in his compromised condition he became bedridden by rheumatic fever. When he was well enough to walk again he required crutches and struggled with rigid limbs and digits. A kindly violin-maker took him on as an apprentice in order to help him reclaim the fine motor skills in his hands, and when Dewar later chose the path of science, this delicate workmanship experience enabled him to fabricate his own laboratory tools and instruments.

As he advanced in the scientific community, Dewar grew to adore the late Michael Faraday, a brilliant and renowned predecessor at the Royal Institute. In the early 1800s Faraday had discovered that one can persuade practically any gas to liquefy by applying high pressures and ice baths. Faraday’s techniques were capable of reaching temperatures as low as -130°C, but despite his ingenuity, three of the gases he tried—oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen—persistently resisted the phase change to liquid. After many failed attempts Faraday tentatively concluded that these three must be “permanent gases.”

By James Dewar’s day, scientists with more sophisticated yet still quite quaint equipment were finally liquefying oxygen at -183°C, and nitrogen at an astonishing -196°C, all without the benefit of electricity. They accomplished this by exploiting the Joule-Thomson effect, “Thompson” being the same man who later became Lord Kelvin. The Joule-Thomson effect describes the tendency of most gases to cool when they are allowed to expand through a valve. This offered an opportunity to chill substances in stages using a series of gases that are each more difficult to liquefy than the last. Experimenters employed pumps to compress each gas into separate holding tanks, then they used ice baths and heat exchangers to lower the temperature of each filled tank. Once each compressed gas was sufficiently chilled, the “cascade” process would begin.

To start the process, the valves on the first tank were opened, expanding the gas into a larger enclosure. This rapid expansion would cause the already cold gas to condense into even colder liquid. This liquid would then be used as the coolant to chill the still-compressed gas in the next tank as much as possible, such that when that gas was expanded into its own sealed vessel it would reach even colder extremes. This would then be used to cool the third gas, and so on. As experimenters pressed closer and closer to absolute zero, each degree of heat became more difficult to squeeze out than the last. All that remained to liquefy was hydrogen—an odorless, colorless gas which tends to turn into a universe if left alone for a prolonged period. Scientists at the time expected that hydrogen would not liquefy until -250°C, within spitting distance of the coldest possible temperature in the universe. It was a monumental undertaking for the time, and it would require yet-to-be-invented apparatuses, but he who would be first to liquefy the last remaining “permanent gas” was sure to be showered with scientific acclaim for advancing humanity’s knowledge of the the properties of matter.

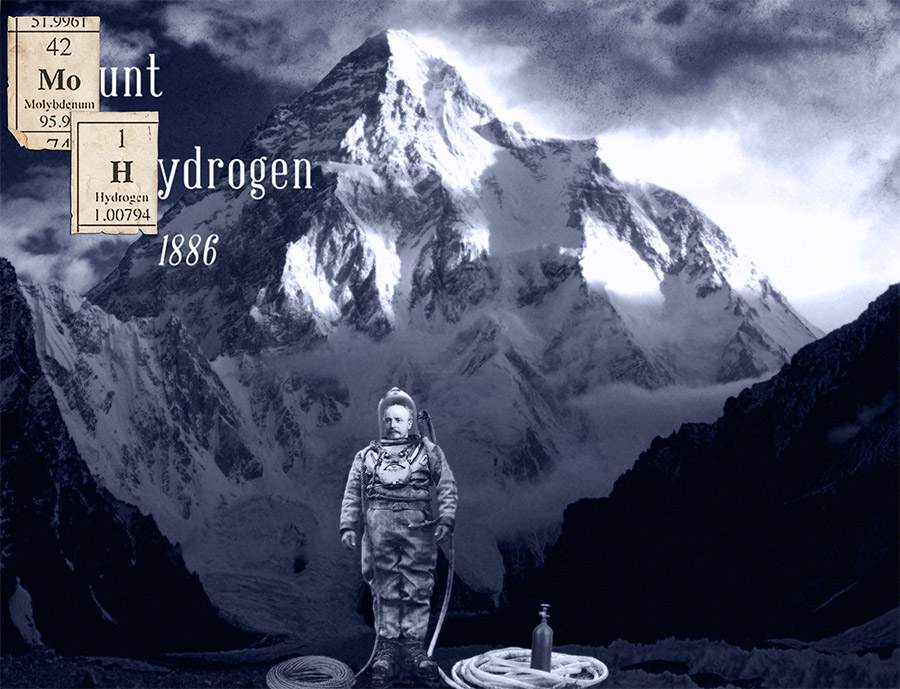

James Dewar was fond of referring to this challenge as “Mount Hydrogen.” Only a few facilities in the world had the equipment and aptitude necessary to even hike the foothills of Mount Hydrogen, let alone glimpse its summit, yet a number of chemists were beginning to clamber. Dewar knew that if he could be the first, his name would be whispered in the halls of the Royal Institution alongside the great Michael Faraday’s for decades—perhaps centuries. Thus in the mid-1880s Sir James Dewar decided to direct all of his considerable scientific and engineering resources into cryogenic research for the purposes of liquefying hydrogen.

Unfortunately, one of the resources Dewar lacked was a sense of tact—he smugly ridiculed the missteps of other aspiring liquefiers in his public remarks and essays. But one fellow scientist somehow escaped his condescension—a massively mustachioed Dutchman named Heike Kamerlingh Onnes. Onnes was a brilliant and ambitious younger scientist with a laboratory at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. He was far behind in the race for liquid hydrogen, but he was making slow, steady advances which he open-sourced for the benefit of all contenders. This was in sharp contrast to Dewar’s tendency to be secretive and hide key components from laboratory visitors. Dewar was also an old-school do-it-yourself scientist, whereas Onnes preferred to employ an assembly line of assistants to fabricate his instruments. Dewar also silently scoffed at his younger colleague’s insistence that experiments should always be preceded by meticulous theorizing and calculations. But despite their differences, in true Victorian-era gentleman-scientist tradition, the two exchanged frequent correspondence across the Channel regarding their research progress and chronic health problems. The Dutchman clearly admired his elder colleague from London, and Dewar clearly shared (rather than reciprocated) this admiration.

Dewar and Onnes were both gradually assembling and rejiggering similar apparatuses based on the cascade method using the best available technologies. This cascade cooling theory was quite sturdy on paper, but in practice its execution was rife with peril. Sometimes liquefied gases would freeze solid in the lines, disrupting the delicate plumbing. The extreme low temperatures caused even the strongest holding tanks, tubing, valves, welds, and connectors to become fearfully brittle. Moreover, many of the most effective cooling gases were highly flammable, as was the hydrogen itself. Not to mention they were being held for long periods at very high pressures. Consequently each ever-evolving multi-ton collection of handmade and scavenged parts was a persnickety and treacherous assembly.

As the experiments progressed, James Dewar conducted a series of public lectures to demonstrate the properties of the coldest liquids he had so far managed to produce. The special “Dewar flasks” he used to handle these liquids were his own invention, a glass vessel with a gap of vacuum trapped between the inner and outer walls. The Scottish scientist dipped ordinarily flexible objects into liquid nitrogen, and then shattered them like glass. He produced a flask of bluish liquid oxygen—which boiled boisterously at room temperature—and used it to flash-freeze a vial of alcohol. Lastly he placed a lit candle in the steam of liquid oxygen vapors, which elicited a dramatic flourish of flame. He concluded these low-temperature demonstrations by explaining to the audience that science was pressing ever closer to the coldest possible temperature, whereupon the molecules would become entirely still, and the “death of matter” was likely to occur. Vigorous applause ensued.

In 1886, James Dewar was entertaining guests at his Royal Institution laboratory in London when a lady asked whether it was true that he was able to condense oxygen. To demonstrate, the Scotsman expanded some compressed oxygen into a tube submerged in coolant, and the lady looked on in awe as the air itself condensed into a pale blue fluid. Unfortunately, there was a leak somewhere in the system, and the oxygen was allowed to mingle with the coolant—liquid ethylene—which oxidized violently. “The mixture caught fire and there was a terrible explosion,” Dewar wrote in a later letter to Onnes. “I was nearly killed and as the experiment was being performed before a number of people, several got hurt.”

As James Dewar recuperated from his injuries, Kamerlingh Onnes became a source of serious concern. The younger up-and-comer was rapidly and enthusiastically closing the research gap, imperiling Dewar’s imminent eminence. Onnes offered to come visit the London lab, but Dewar informed him that he if he did so he would not be allowed to set eyes upon the secret cryogenic equipment. Dewar felt he was within sight of the summit, and was reluctant to lend an accidental hand. Despite his ill health and injuries, Dewar resumed his low temperature research as soon as he was able, placing himself back in the midst of what he described as “difficulties and dangers of no ordinary kind.” These dangers again became evident in 1896 when a pressure gauge burst during a low-temperature experiment, flinging glass and shrapnel into the face of Dewar’s loyal laboratory assistant Robert Lennox. The incident cost Lennox an eye, yet he persevered. For science.

In March 1896, just when these laboratory calamities seemed certain to steal Dewar’s scientific prize, he received a letter from Kamerlingh Onnes, wherein the Dutchman confided:

I have not been able to repeat your splendid experiments for since your last letter it was impossible for me to work at low temperatures and that for a reason you will be astonished to hear. The municipality of Leiden has made objections as to my working with condensed gases and has not been content with asking that additional means of precaution are taken, but is gone so far to claim in August last that my cryogenic laboratory be removed from the city! Not withstanding that never any notable accident happened in all the years I have been working there…

Dewar replied, decrying this “great disaster to science,” and sent a letter to the Leiden town council complaining of the same. But as Onnes contested the banishment of his gases, Dewar had time to perfect his cascade cooling system. The lab installed a 100-horsepower state-of-the-art gasoline-fueled pump, and on the 10th of May 1898, James Dewar and laboratory assistants Robert Lennox and James Heath prepared their cantankerous contraption for an attempt. The scientists began by opening the valve on their compressed chloromethane, and expanded it to cool a tank of ethylene. This they expanded to liquefy a quantity of oxygen, which in turn was used to chill a canister which held hydrogen gas at an unprecedented 180 atmospheres of pressure. Once the hydrogen tank was at -205°C, the experimenters carefully twisted the ice-encrusted valve.

The gas hissed into the larger expansion tank, with no indication of freeze-ups or clogs. The thermometer steadily fell. Once the reading indicated -252°C, a clear, colorless liquid began to slowly but steadily drip into the glass collector at the bottom of the expansion tank. This continued for five minutes, until a nozzle froze up and forced the experiment to an end. James Dewar took a small vial of the liquid oxygen and submerged it in the new fluid. The pale blue oxygen froze instantly into a pale blue solid. This proved that the twenty cubic centimeters of liquid in the collector was indeed hydrogen. Dewar had done it. Thanks to a decade of effort he had created the coldest and stillest moment in spacetime the Earth had ever seen, just 21 measly kelvin above absolute zero. He had bested the upstart Dutchman, and he’d done what the great Michael Faraday had once deemed impossible. He had liquefied the final available “permanent gas,” and secured his place in history.

Or, so he thought. The anticipated acclaim did not materialize.

His accomplishment, it turned out, had been eclipsed by another discovery: chemists had identified yet another elemental gas whose liquefaction temperature was even lower than that of hydrogen. This new gas, helium, had been hypothesized to exist based on known elements and spectroscopic observations of the sun, but failure to find it in nature had led scientists to believe that the element could only be found in stars and gas giants. Indeed, loose helium is so light that it escapes Earth’s gravity and drifts into space, however intrepid sifters had finally begun to find some trapped in rocks, sands, and cavities. Helium became the new last permanent gas, and consequently its liquefaction became the noblest goal.

In the meantime, across the Channel, Kamerlingh Onnes had taken his laboratory closure complaint all the way to the Supreme Court of the Netherlands, and emerged victorious. The Dutch scientist dusted off his liquefaction machine and began mobilizing his own resources. Adjacent to his laboratory building he established the Society for the Promotion of the Training of Instrument-Makers, and set these “blue boys” to work improving his massive cryogenic apparatus. Using Dewar’s system as a guide, Onnes and his crew constructed their own high-volume hydrogen liquefaction plant with the intent to use its output as a coolant to produce liquid helium. But helium gas proved frightfully difficult to come by. Onnes learned that the great James Dewar had found that the sands surrounding Bath Springs held some trapped helium, and that Dewar had devised a process to extract it. The Dutchman wrote to propose an alliance. He offered to share his data, his calculations, his huge liquid hydrogen supply, and the cost of helium extraction all in exchange for access to the elusive gas. Dewar replied:

We both want the same material in quantity from the same place at the same time and the supply is not sufficient to meet our great demands. It is a mistake to suppose the Bath supply is so great. I have not been able so far to accumulate sufficient for my liquefaction experiments. If I could make some progress with my own work the time might come when I could give a helping hand which would give me great pleasure.

Sir James Dewar’s supply was not quite as scarce as he suggested, but he had labored alone for far too long to go Dutch on the byline. Aged 62 and suffering from strained health and budget, he supervised the extraction of helium from the sand supply, a slow and tedious process which involved freezing it with liquid hydrogen and exploding it with oxygen. This would liberate a scant few helium atoms which were then trapped by a charcoal filter.

By 1903 he finally had collected enough of the gas for an attempt. The updated cryogenic system was even more complex than before, a massive sprawling cold factory festooned with valves, canisters, vents, and pipes. The scientists connected their precious compressed helium canister to its inlet and used their liquid hydrogen supply to refrigerate the container. When they opened the valve to expand the helium itself, some impurities in the gas froze solid inside the tubing and impeded the flow. An unspecified assistant with quick reflexes reversed the helium valve, but he turned it either the wrong way or too far, because instead of halting the flow of helium, he caused it all to be vented into the laboratory. Dewar’s notes do not indicate whether a high-pitched apology was offered.

Coincidentally, Lord Rayleigh and Sir William Ramsay had a laboratory just next door to Dewar’s, and these gentlemen had access to some helium. However they were also among the many scientists whose egos had been previously dashed upon the rocks of Dewar’s scorn. His deficit of decorum left him few friends. Dewar’s fortunes continued to deteriorate when his London lab was rattled by yet another minor explosion which deprived yet another lab assistant (James Heath) of yet another eye.

In the early dawn on the 10th of July 1908, Kamerlingh Onnes and his assistants gathered at their own low-temperature laboratory in Leiden. Onnes had found his own source of helium-laced sand from North Carolina, and he had patiently spent the intervening years extracting and gathering his own supply of the scarce element. Onnes and his “blue boys” filled every spare space in their vast apparatus with liquid hydrogen for insulation. They had pre-prepared their array of compressed gas canisters the evening prior. As word of the intent to liquefy helium spread through the university campus, a small crowd gathered at the laboratory to observe. Onnes’s wife arrived with sandwiches in the afternoon, but he was too busy to pause for nourishment, so she followed him around the lab thrusting bite-size portions into his mouth as he shouted orders and supervised the preparation of the machine.

At 4:20 in the afternoon, the critical parts of the assembly were awash in liquid hydrogen, and the men opened the main helium valve. Their lab compressor chugged away noisily, applying a gradually increasing pressure inside the expansion tank to increase the likelihood of helium condensation. Through the remainder of the afternoon and into the evening the scientists continuously replenished the liquid hydrogen coolant, and watched the thermometer as it crept down toward the temperatures where helium was expected to liquefy. As they poured in the last few drops of their liquid hydrogen, Onnes was clearly concerned—although his equipment had achieved the unheard-of low temperature of 5 kelvins, the temperature reading had been stuck there for some time, and no liquid could be seen in the glass collector. Perhaps something was wrong. One of the onlooking professors suggested that the temperature might not be changing because the thermometer might just be submerged in a liquid. Onnes grabbed an electric light and hunkered down next to the glass reservoir. There, with the help of the light, Onnes became the first person on Earth to see liquid helium. The scientists had not anticipated that liquid helium’s index of refraction would be so extraordinarily low that it would be difficult to see in ambient lighting.

Onnes hastened to make observations with the small container of -271°C fluid before it all evaporated away. He found it had a lower surface tension than any previously observed liquid, and just 1/8th the density of water. The modest amount of the stuff he had been able to collect behaved very curiously in general, flowing with strange characteristics and evading easy observation as if enveloped in an SEP field. It was impossible for him to know that he had created a rare and fleeting superfluid, a previously unseen state of matter. The viscosity, or thickness, of a liquid is caused by dissipation of energy due to friction between particles, but since superfluid liquid helium is already in its lowest state it cannot dissipate energy, and it therefore must flow with zero resistance. Quantum mechanics insists.

Kamerlingh Onnes dispatched a telegram to his cryogenic colleague in London to share his exciting news. The telegram he received in reply was heartbreak couched in courtesy:

CONGRATULATIONS GLAD MY ANTICIPATIONS OF THE POSSIBILITY OF THE ACHIEVEMENT BY KNOWN METHODS CONFIRMED MY HELIUM WORK. ARRESTED BY ILL HEALTH BUT HOPE TO CONTINUE LATER ON.

Dewar was less circumspect with his pair of one-eyed laboratory assistants. He tongue-lashed Robert Lennox for failing to find a more abundant helium source, and Lennox stormed out, vowing never to return to the Royal Institution until James Dewar’s bones were cold in the ground. He proved to be a man of his word.

It would be 15 years before any other researcher was successful in manufacturing liquid helium. In the meantime Onnes used his helium monopoly to study the effects of near-absolute-zero temperatures on various materials. He discovered that some materials such as mercury were able to conduct electricity with zero resistance at 1-2 kelvin above absolute zero, a phenomenon he dubbed superconductivity. This is the very property that enables some of the most advanced modern technology, such as MRI machines, magnetically levitated trains, and particle colliders.

Despite his considerable contributions to science, Sir James Dewar was never awarded a Nobel Prize, though he received nine nominations. Instead, scientific spoils went to the people who built upon his work. For instance, Lord Rayleigh and Sir William Ramsay used Dewar’s liquid hydrogen as a tool to discover the elements xenon, neon, and krypton, and they won the 1904 prize for Chemistry. Kamerlingh Onnes himself won the prize in Physics in 1913 for improving Dewar’s liquefaction strategy for helium. In his Nobel lecture, Onnes credited Dewar for having been the first to liquefy hydrogen, and for having revolutionized low-temperature research with his ingenious vacuum flask. But even the Dewar flask brought its namesake some vexation—a glassblower he had hired to make some of the first such flasks became so fond of the design that he used the sincerest form of flattery to found the now-famous Thermos company. A lengthy court battle finally decreed that Dewar was entitled to credit for the invention, but not owed any damages. But most scientists today still call these flasks “Dewars” in his honor. The curmudgeonly maverick even filed a suit against the famous Nobel family, claiming that their explosive innovations were based on his earlier chemistry, but the judge dismissed the claims. Dewar never retired, and he maintained the position of Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution until his death on 27 March 1923.

Kamerlingh Onnes died in Leiden about three years later on 21 February 1926. He did so with the full awareness that he was among the last of a disappearing breed—the “classical physicists” who had the luxury of simply banging on matter until it did interesting Newtonian things. Science was thenceforth in the capable hands of quantum mechanics. His helium liquefaction apparatus remains on display to this day at Leiden University.

In 1937, researchers Pyotr Kapitsa and John F. Allen first formally observed and described the strange superfluid state of liquid helium that Onnes had lacked the foreknowledge to identify. They found that when one chills liquid helium below the lambda point—2.17 K—the boiling liquid falls suddenly, eerily still, and it takes on bizarre properties. The individual helium atoms blur into one another and become a single “superatom”, also known as a partial Bose-Einstein Condensation (BEC). This is a demonstration of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, which states that the more precisely the momentum of a particle is determined, the less precisely its position can be known. Since particles below the lambda point have almost no movement, their momentums are almost entirely “known,” therefore by necessity their positions become so inexact that they begin to overlap one another. In this situation atoms stop behaving like discrete things and become ambiguous smears of quantum probabilities. If one physically scoops up a portion of the superatom, the elevated portion acquires more gravitational potential energy than the rest, and since this is not a sustainable equilibrium for the superfluid, it will flow up and out of its container to pull itself all back into one place. It also flows with zero friction, as Onnes observed, since it has no energy to lose. Matter is indeed strange stuff—it’s just seldom so obvious.

Researchers today are tinkering with temperatures below one kelvin at extremely high pressures in order to freeze helium into helium ice, which may ultimately reveal a never-before-seen theoretical supersolid state. If the theory turns out to be correct, supersolids may make a mockery of the very notion of solidity since they will also be governed by the uncertainty principle. A chunk of helium ice would behave as a single, solid, oversized, and stupefyingly slippery atom, which may be capable of passing ghost-like through certain materials. But that’s another matter altogether.

As of this writing the coldest temperature ever reached on Earth occurred in 2003 when MIT scientists chilled a cloud of sodium atoms to 0.45 nanokelvin—about one half of one billionth of a kelvin above absolute zero—using lasers, evaporative cooling, and “gravito-magnetic traps.” And NASA is planning to routinely reach one ten billionth of a kelvin aboard the International Space Station (ISS) in the Cold Atom Laboratory, first activated in 2018. On Earth, Bose-Einstein condensates fall apart within fractions of a second due to the pull of gravity on the atoms—but in the microgravity on the ISS, these condensates will linger longer, permitting observation for up to six hours at a time.

Modern scientists are confident that absolute zero itself is an absolutely unattainable temperature, as it would require an infinite amount of time and energy to squeeze out the last tiny fraction of heat energy. Nevertheless, there is nothing cooler than seeing science press up against the very boundaries of the physical laws of the universe, and to see how curiously things behave there.

© 2014 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/absolute-zero-is-0k/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://www.damninteresting.com/donate ?

**FIRST**

Keep ’em coming folks. Another fine read.

That may be the coolest Damned Interesting I’ve ever read, pun intended. XD

Great article!

Great article……..This one will be shared.

Definitely the most interesting article lately! Here you can find a very interesting series of instructional videos about the curious properties of liquid helium:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OIcFSHAz4E8&list=PL47186D8A68FDA6DE

I had a lot of tasks recently and therefore I didn’t have enough time to come after work, finish all my overdue stuff, relax, waste some time, get bored and finally awake the curiosity hidden deep in myself, that used to drive me when I was younger. Often when stumbling upon interesting stuff, I promise to myself that I will study it in a free time, but eventually I just forget about it.

Today I returned home with a minor headache that would normally cause me to have a nap just after checking e-mails, but as an e-mail from DI came with not only *cool* but also a catchy title, I felt an urge to see if 0K was achieved (of course not, but still: I didn’t know scientists came so close to it already). Eventually, unique style of DI articles sucked me into the tale of heroic tinkering.

I know your secret, Alan. You just put a lot of effort into your research and writing the article. That’s why I donated and I hope the audiobooks are indeed professional – my money wouldn’t be wasted anyway, but your work deserves to be read by a good voice.

Thanks! Although, note that the video you linked is the same as we have in our not-altogether-accurately named “Further reading” section at the foot of the article.

Confirmed again that you do your research well:)

0.45 nanokelvin isn’t just the coldest temperature ever on Earth, it’s the coldest temperature ever *in the universe*. Even empty space has a temperature of 2.7K due to the cosmic microwave background. Unless there’s a more-advanced alien species out there doing cryogenics research, there has never, in the history of time, been anything cooler.

I didn’t realize Edward Snowden was among our readers. Heh.

I left wiggle room for precisely that possibility…we may not be the first species to try.

Totally engrossing, as always. Great title! Favorite giggle: “Dewar’s notes do not indicate whether a high-pitched apology was offered.” Thanks, Alan!

DI! Thanks Alan.

Another fine article Alan! DI!

Damn Awesome!

Excellent article! It occurs to me that the described technology could be put to more practical use. Perhaps in the cooling of homes on hot summer days. Sort of air conditioning…….oh….wait a minute. How about for the chilling of liquid refreshments then? Dewar’s Scotch Whiskey springs to mind for some reason.

Heh… Nice “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” reference. Took me a moment to recognize the reference to the “Someone Else’s Problem” field.

Interesting article, especially how the social aspects may have affected the science as well.

Side note: Technically there are “negative Kelvin” temperatures, but oddly enough they’re not found below absolute zero. Despite what the phrase might lead you to believe, “negative Kelvin” temperatures are actually absurdly hot, somewhere over infinity Kelvin. This is because of a very weird quantum effect, where some quantum system’s temperatures can be so hot that they decrease their entropy as more energy as added, instead of increasing their entropy as we normally observe. It’s kind of like getting to a level so high in “Pac-Man” that the game starts acting weird. These ultra-high temperatures are referred to as “negative temperatures” on the Kelvin scale. See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negative_temperature

You guys think a ten-thousandth of a nano-Kelvin is cold?

Obviously, none of you have ever met my ex-wife.

;-)

Jim

Sunk New Dawn

Galveston, TX

Your description of hydrogen is absolutely brillant !

This qoute, has got to be one of the funniest and yet scientificly correct statments made on the internet

hydrogen–an odorless, colorless gas which tends to turn into a universe if left alone for a prolonged period

I read this about 4 days ago, and I was in the shower last night and the brilliancy of the title finally hit me. I read it as ‘ok’, but then I realised… absolute zero is literally ‘0k’. Amazing… just amazing :D

I think this is perhaps the best Damn Interesting article that I have read. Thanks Alan.

Great article! Glad to see ya’ll back at it once more.

Greetings from India. I typed “something to read” in google and reached DI. I’m so glad I found you.

The articles are not just informative but very entertaining too. Keep up the good work!

Mayan

Excelent article,most definatly D.I. looking forward to the next item.keep up the good work ;)

Here is an awesome NOVA that covers all of this stuff and the modern efforts to create a Bose-Einstein condensate: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1wBWtUG2uY

Alan, thank god a new article. I was suffocating! I learned something new, Helium turns into 1 atom? Amazing.

If you’re looking for a new article idea, check out the FBI Vault, or “The Vault” and have a look-see at Amelia Earhart. 2 men and their stories.

I would hope it’s not Damned

Awesome one! great read, thanks :)

Thanks for this side note. I am and English teacher and I am using this article as a close read for a teacher training because its just wonderful and the vocabulary choice by the author is fabulous…anyways, I was unsure of what OK meant and I figured it was associated with absolute zero somehow…yep, it is. Appreciate the side bar. Now I will appear more scientific while I give my presentation.

Are you familiar with http://www.reddit.com/r/Showerthoughts/ ?

This is a high compliment…thank you.

Dear sir/madam.

There is another matter/element that might be interesting when condensed to a gas, liquid, and ultimately solid form and that’s the Neutron. I admit I’m a layman when it comes to the subject of nuclear physics but once humans learn how to contain them in large volumes i would have thought an element with no electrons or protons at all would do a few interesting things. I mean in theory you could stick it in the middle and on the outside of an atomic warhead core for example and use it as a hyper initiator. Press the fire button attached to the explosive lenses and drop the containment field at the same time: Result flood of neutrons heading inwards and outwards, more Plutonium atoms being split as the warhead expands. Or do something more sensible like use them to boost the reaction inside a Tritium-Lithium 5/Lithium 6 Fission Fusion reactor. Admittedly a shell made of atomic waste would probably supply enough Neutrons to feed the reaction but.. Anyway. Thanks for reading. Hope the links OK. Hope i haven’t gone of subject too much.

Yours sincerely.

Mr Alpha Omega. AKA Andy.

http://periodictableofelements.wikia.com/wiki/Neutronium

Ps. Brilliant article. Well done yet again.

This is one cool read. One of the most interesting 15 mins that I have spent. Keep it coming guys.

This is an odd method of demonstration, considering that since the input gas was pure hydrogen, the liquid had to be hydrogen.

Since there was apparently already a thermometer that showed the temperature, I suppose that Dewar wanted to dramatically (of course) show that the temperature of this liquid was definitely below the lowest known freezing point.

Awesome article!

Can someone explain “tends to turn into a universe if left alone for a prolonged period”?

Increible article; damnably interesting.

And nice Hitch Hiker’s Guide reference too :-p

“All that remained to liquefy was hydrogen–an odorless, colorless gas which tends to turn into a universe if left alone for a prolonged period.”

Heh. Brilliant writing.

A very “cool” article. Missed DI for a long time. Hope you continue consistently with more fantastic stuff to read.

Haha, I wasn’t. But I am now. Thanks :)

LOOOL!

Best article ever

My favorite of Alan’s (many) puns:

“But that’s another matter altogether.”

(On the topic of supersolids.)

The pain of scientific discovery. What initially seemed to a game of upping one another, provided the fuel to embark upon one of the most fascinating journeys. I remember Dewar’s flask but I am saddened to know that the work of the genius was cut short by his tongue. Quirks of being a genius I suppose.

This is a fantastic article and I felt I was witnessing the events unfold. Keep up the great work!

Hi Damninteresting team,

It’s a damn good job you have done (& you are continuing doing that). It is just next best to wikipedia. Superb guys…Carry on !!!

Now, coming to the business part, I wish to be a part of your team & post such damn interesting facts by adequately researching on them. Then it will be up to the discretion of u guys, whether they are “sufficiently” interesting or not.

Hopefully I will be able to contribute, at least in terms of posts, beacuse in terms of donations, I am currently unable to do so…:)

Please send me the details if you guys are interested.

Thanks

Samikshan

Fascinating and Intoxicating article…

Gratitude

Big Bang Cosmology posits that pproximately three-quarters of the ions created in the first twenty minutes or so were hydrogen. About a billion years later all that hydrogen began to coalesce into stars pumping out the heavier elements that make up everything we are observing thirteen billion years later. How’s that for condensing fourteen billion years of history into two sentences?

This is awesome.

Fantastic article- both content and form! Was a pleasure to read.

Had one questions as well….the original scientists liquefying these gasses, taking them down to -250C, which were the thermometers that they used to actually measure down almost to absolute zero?!

Greetings form the Czech Republic

I couldn’t sleep tonight and while randomly browsing I stumbled upon this site. I have to say that that all the articles here are indeed pretty damn interesting and particularly this one is one of the best I’ve read in a long while.

“hydrogen–an odorless, colorless gas which tends to turn into a universe if left alone for a prolonged period” – the best description of hydrogen I’ve ever heard, that sentence actually made me lol.

Keep up the great work, I wish there would be less cat videos and more sites like this one on the world wide web.

Great article!

According to the big bang theory, just after the bang, as the universe cooled, everything condensed into hydrogen gas. So the universe started out with one single element, hydrogen. As time progressed, gravity caused the hydrogen to collapse into the first stars and start the fusion process. This process produced all the other elements in the universe.

So take a bunch of hydrogen and let it sit for a really long time and you will get the universe. You would have to have a really large amount of hydrogen and it would take a while. Maybe best if you plan on having something else to do while you wait.

The Big Bang shattered absolute zero. Charles Talley

This article is interesting, it made me learn a lot

Great read! One question remains: WHAT did they use for thermometers?

Interesting article and well written, in my opinion, but it still does explain where my d*** goes in the winter.

Scientists claim to have reached “below absolute zero”. You can google that. It seems impossible but according to them our Kelvin scale isn’t perfect. They say their “cooled” gases are actually hot but their temperature is below absolute zero.

@Asad Ali: While physicists have reached negative absolute temperatures, one could not correctly say that they have reached temperatures colder than absolute zero. Absolute zero is still the coldest that matter can theoretically become. My first draft of this article had some discussion on negative temperatures, but I cut it out because it seemed too tangential. I did some research on negative temperatures, and this is my understanding:

In normal mathematics, numbers begin at negative infinity, count up to zero, then continue on to positive infinity. This is not the case with temperatures since there is an absolute lower bound (absolute zero). In most materials most of the time, the absolute temperature scale just goes from zero to infinity. But there are some circumstances where atoms have an upper bound to how much energy they can absorb, which causes a weird effect. Imagine dividing the classical numbering scale at zero, so you have a part on the left that represents negative infinity through zero, and a part on the right that is zero through infinity. Now swap the two parts left to right, and you get a number scale like this:

0,1,2,3,4 … infinity,negative infinity, … -4,-3,-2,-1,-0

It starts at zero, counts up to infinity, then switches to negative infinity, and counts ‘up’ to negative zero. This is how temperatures can behave in those aforementioned atoms under certain circumstances. As you can see, even though the temperature is ‘negative,’ it’s well above absolute zero. Physicists used lasers to trap some atoms in an ‘optical lattice’ which imparted this upper energy bound, added energy until they crossed the upper bound, and observed that the atoms behaved as they would at negative absolute temperatures.

More detail here (including possible connection to dark energy):

https://www.quantum-munich.de/research/negative-absolute-temperature/

Yay science!

Does the OK mean One Kelvin?

An absolute article. On an absolute zero. Absolutely fascinating reading. Thanks for this absolutely fine tooth research that is spot on zero.

“Dangers be damned, there was science to be done.”

DI read as always.

Just stumbled upon this blog, and my my.. it *is* damn interesting indeed. Love your writing style, and respect the effort that you take. I cannot single out one, every sentence or phrase used is a gem. Registered just to post this comment. Thank you for refreshing my day :)

Mr. Bellows:

Hard to believe that I missed this one – I’m extremely glad that you reposted it because it is an incredible read.

About a year ago, I saw a special on History about this very topic. I think that they used your article as the script.

I love re-reading the articles – thanks for posting it again!

Just checking in again.

I’m back.

And again.

I am here.

I came to understand the coldness of absolute zero the most completely while dating a girl in college for a few weeks.

Just checking for other posters.

I wish that someone else would also post.

Now that I think about it, absolute zero was my chance of having sex in high school.

Checking back in.

Back again.