© 2006 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/the-bridle-on-the-neck-of-the-sea/

This article was written by Zack Jordan, one of our shiny new Damn Interesting writers.

In the grand old year of 1492, Christopher Columbus set out from Spain with a fleet of three tiny ships. His journey began in August of that year, but it was March of the next before the Old World heard from Columbus again. Time taken: nearly eight months.

Over a century later, in September of 1620, the Mayflower departed England on its historic voyage to the New World. In May of 1621, it returned, bearing news of a (relatively) successful mission. Total time taken: more than nine months.

Over two centuries after the Mayflower, in 1850, the western world was in a state of dynamic change. The Industrial Revolution was in full swing, and the world was optimistic. The first railroads had been operating profitably for over a decade, steamships plied the rivers and coasts of America and Europe, and a network of telegraph wires had spread across territory on both sides of the Atlantic. Where once it had taken weeks to transmit news across hundreds of miles of land, it now took minutes. The world, it seemed, had shrunk. And between the two continents, where once it had taken months to deliver news, it now took… months. Nineteenth-century communications had hit a brick wall; the fastest way to get a message across the Atlantic was still floating and steam-powered, and it looked like things were going to stay that way unless someone was willing to take some huge risks.

As well-connected as Europe and America were internally, they were still cut off from each other just as effectively as they had been for centuries. Even with the advent of the steam ship, Atlantic crossings were still risky and of unpredictable length. Fortunately for the mid-eighteenth century, there was one man who not only saw the possibility of instant trans-Atlantic communication but was willing to put his formidable assets to work to make it happen.

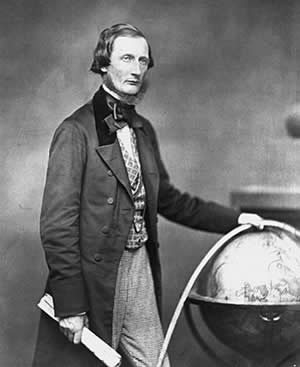

Cyrus Field was the embodiment of the Victorian American dream. He was a self-made man with a taste for business, and one of the wealthiest men in New York City. He also had the benefit of nearly limitless charisma, drive, imagination, and— some would say— blockheadedness, all of which proved to be indispensable for the project. He was a rare example of a brilliant businessman/salesman with a philanthropist’s heart.

Fortunately, both sides of his personality saw the benefit of trans-Atlantic communication. Of course there was plenty of money to be made, but Field knew that good communication could solve many of the problems between distant countries. For example, the bloodiest battle of the War of 1812, while technically an American victory, was fought two weeks after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed; this event and others like it offered proof that news in the nineteenth century simply couldn’t travel quickly enough. Armed with his notable charisma, Cyrus was able to collect enough investors to begin the project by 1854. Initially, the sum of $1.5 million dollars was pledged to the project. In contrast, the entire budget of the United States that year was under $60 million.

This monumental feat of engineering required technology that was not only in its infancy- it was derived from technology barely into its toddler years. No one knew if it was even possible to send a signal through more than two thousand miles of cable. The concept of resistance, while known, had not yet been scientifically defined. No one knew how much an armored electrical cable weighed, or whether any ship in the world had the payload capacity to carry its entire length.

Fortunately, Cyrus was ignorant about all of this. He hired the best minds in the world- including Samuel Morse and William Thomson, later known as Lord Kelvin- and told them to make it happen. Field’s small group of engineers would soon learn that a well-armored nautical cable weighs over one ton per mile- resulting in a total weight of nearly 2,500 tons to span the Atlantic. Adding to this problem was the fact that no ship currently in existence had a payload of 2,500 tons.

For the first three attempts, steps were taken to reach a compromise between cost and quality. Corners were cut during the construction of the cable, and two ships began the massive undertaking of laying it. Unfortunately, the results were not encouraging. During the first two attempts, the cable snapped due to machinery inadequacies which were heightened by rough weather. The third attempt was a technical success, but the cable stopped working less than a month later. This failure was blamed on an operator who upped the potential to several hundred volts, blowing a hole in the cable somewhere in its two-thousand-mile length.

For the fourth and fifth attempts, Cyrus Field was able to purchase a ship- and not just any ship. Cyrus purchased the largest ship in the world, the recently-built Great Eastern. And if this in itself does not seem impressive, consider that this massive vessel held the distinction of being five times the size of the next biggest ship in the world. This was the nautical equivalent Spruce Goose, dwarfing all other seagoing craft and weighing in at 32,000 tons. The extra weight of the cable was a drop in the bucket of this Leviathan.

After ten years of effort, using this monstrosity of a steamship as well as the technology that had been developed in response to the previous failures, everything came together on July 28, 1866. The Atlantic Cable was stretched across the ocean floor from Ireland to Newfoundland, a distance of two thousand miles. It was a resounding success, wildly celebrated on both sides of the Atlantic. Speeches were made, songs were written, and the public’s appetite for instant communication was whetted. Within months, another cable was laid. By the end of the century, fifteen cables crisscrossed the Atlantic. It would be nearly a century after the first successful cable was laid that trans-Atlantic telephone communications effectively put the original cable stations out of business in the early 1960s. It is a testament to the brilliance and sheer determination of Cyrus Field that from that day in 1866 to this, America and Europe have never again been out of direct communication.

© 2006 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/the-bridle-on-the-neck-of-the-sea/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://www.damninteresting.com/donate ?

This guy would have LOVED the internet!

Nice first article, Zack. Darn Interesting…

3rd post….woohooo!

How much the world changed in a hundreed years…

This, in my opinion, had more of an impact than the “Chunnel”

On yer Zack! This rates about 8.5 on the DI-o-meter.

The technical problems in getting a (useful) signal through 2000 miles of cable are seriously “non-trivial.” I learned about the problems with the first trans-Atlantic cable many years ago – but never thought to dig up the finances of the project. Does anyone know if Cyrus blew his entire fortune on this hare-brained scheme, or if he died a rich and happy man?

To see how rapid communications really affected the world, check out “The Victorian Internet” by Tom Standage.

Of course he died a pauper – it seems all rich men from that era did. See the Wikipedia article on him. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_Field

The biggest reason the initial cables were a failure was because Cyrus’s chief electrician didn’t know what he was doing. All the cables laid were just single line, and without getting into detail, single lines in water, even insulated, greatly retards the signal going through it. You need a coaxial cable. Several scientists had told him this beforehand, but the guy was adamant that it would work. Well, it didn’t.

Anyway, it’s actually kinda funny how little the concept has changed since then. Just now it’s done with fiber a lot faster.

We’ve come a ways from Field’s cable to the FLAG (Fiber-optic Link Around the Globe), but it wouldn’t have happened without what everyone has learned from those pioneering efforts… DI, Zack! Good first article.

Kudos, Zack. Well done. :-)

^5 Zak DI…I wonder if any one has bothered to salvage all that abandoned cable on the ocean floor.

That’s really well written and very interesting… I can see why I didn’t get the place :-P Well done.

Its kind of amazing how far we’ve come in just the last 150 years. Cant wait to see what else is coming

Great article Zack, and definitely Damn Interesting. I wondered how trans-Atlantic communications got started, and who was brave enough to try that first 2,500 mile span, and now I know :)

Damn Interesting, to be sure. One minor quibble, if I may – not certain that America “won” the War of 1812. Not sure anybody did (unless you mean “win” in the Hezbollahian-sense, I suppose – America survived). Perhaps an idea for your next DI article? That both Canada and the US claim they won that war?

well done and damn interesting. good show

philtlucre said: “Damn Interesting, to be sure. One minor quibble, if I may – not certain that America “won” the War of 1812. Not sure anybody did (unless you mean “win” in the Hezbollahian-sense, I suppose – America survived). Perhaps an idea for your next DI article? That both Canada and the US claim they won that war?”

Canada sucks.

A-Train72 said: “Canada sucks.”

Maybe but we did burn down your white house. :P

philtlucre said: “Damn Interesting, to be sure. One minor quibble, if I may – not certain that America “won” the War of 1812. Not sure anybody did (unless you mean “win” in the Hezbollahian-sense, I suppose – America survived). Perhaps an idea for your next DI article? That both Canada and the US claim they won that war?”

Zach wasn’t claiming that the USA “won” the entire war, only the Battle of New Orleans which took place in the two months following the signing of the Treaty of Ghent. Nobody, from either side, needed to die in that conflict, since it shouldn’t have taken place if only word of the treaty had reached the front in time.

Hence the whole point of mentioning it with respect to this article. Well used Zach.

topnotch said: “^5 Zak DI…I wonder if any one has bothered to salvage all that abandoned cable on the ocean floor.”

The cost and resouces that would be expended to collect them would almost certainly outweigh (by many orders of magnitude) the value of the old cable. Aside from doing it “just to clean up after ourselves”, there’s nothing to be gained from such a venture.

Well done, Zach. I’m a telecom engineer from way back, so I knew the deets already: turns out you have a VERY good writing style. The DI guys made a good choice!

Great Joy Zack. Damn Interesting

Impressive writing and a DamnInteresting subject, so KUDOS on both counts. Looking forward to future contributions and continuation of this site. And isn’t it lovely that nobody (so far) has dragged out their SPIRITUALITY to reduce the quality of comment into blathering, provocative twittedness?

Oh yeah…. The title is quite clever, methinks!!!

Great article, pretty much the ‘fish walking on land’

of the internet, the origins of it all. Unless you consider

stringing two cans together and saying, “Mr. Watson,

I need you.” as the beginning of it all.

As far as that silly war in 1812, Canada didn’t exist yet.

Unfortunately for Train 72 that didn’t happen for

another 55 years, 1867 a year after ‘ everything came

together’ between Newfoundland & Ireland.

cornerpocket said: “And isn’t it lovely that nobody (so far) has dragged out their SPIRITUALITY to reduce the quality of comment into blathering, provocative twittedness?”

With that statement, unfortunately, you just did. The quality of one’s spiritual foundations will always come forth within the context of one’s writing/speech/lifestyle. To disdain, celebrate, or tolerate spiritualty is illuminating your own spiritual foundations, which, like it or not, we all have.

Excellent article, Zach!

ChickenHead said: “The cost and resouces that would be expended to collect them would almost certainly outweigh (by many orders of magnitude) the value of the old cable. Aside from doing it “just to clean up after ourselves”, there’s nothing to be gained from such a venture.”

You are assuming scrap value only? I would buy a piece on ebay. I would bet that corrosion has destroyed the original cables by now.

Depends on how armored those cables were. I’ve been trying to find more info on the current state of those cables and I can’t find anything. Just history. Would be nice to find one of the lines in dissuse and fire a few a few packets of data through them. :)

GREAT article!! Very well written, and I’m sure we all look forward to seeing more of your work, General Jordan!

Just how much fibre do you need for a 2,500 mile cable?

I believe at least one of the attempts involved 2 ships trying to meet in the middle, and I also have a vague recollection that they literally dropped the cable to the bottom of the ocean whilst attempting the splice?…Anyone else see this on Discovery Channel?

Nicely done Zack, look forward to the next of your articles!! :)

Thanks for the kind words, everyone. Glad you enjoyed my first article. Hopefully, the best is yet to come…

Illustrator said: “Great article, pretty much the ‘fish walking on land’

of the internet, the origins of it all. Unless you consider

stringing two cans together and saying, “Mr. Watson,

I need you.” as the beginning of it all.

As far as that silly war in 1812, Canada didn’t exist yet.

Unfortunately for Train 72 that didn’t happen for

another 55 years, 1867 a year after ‘ everything came

together’ between Newfoundland & Ireland.”

Canada did exist, just not unified like it is today. There was “Upper and Lower” Canada. Look it up on Wikipedia, it’s interesting.

I’m sorry, did that say 1812 was technically an American Victory?

Anyone holding salt about history should know any claims about a win, being “technical” or otherwise, borders ignorance.

He worked so hard, put so much effort into it, then those idiots went and discovered wireless communication and made his work obsolete. Why even bother, someone’s gonna outshine you in a bit.

alias said: “He worked so hard, put so much effort into it, then those idiots went and discovered wireless communication and made his work obsolete. Why even bother, someone’s gonna outshine you in a bit.”

haha. nice attitude. :D

topnotch, ChickenHead, sulkykid, Puppeto,

I have in my hands something that might interest you. First a little background on why I have it. Back in the 1970’s I served aboard a cable layer/repair ship, USNS Albert J. Myer (T-ARC 6), as a USN radioman. Because of this my father bought and sent this to me. It’s a 4 inch length of armored cable. Is attached to a wooden base with a tag underneath “The Transatlantic Cable 1858”. Short blurb on the back mentions this is from the first TA cable that only worked about a month. Looks like 6 conductor copper in the center surrounded by armored cable which is itself surrounded by yet another layer of armored cable. Is approximately 11/16 inch in diameter. The back mentions two places you may be able to get some info.

National Museum of History and Technology Smithsonian Institution, and Award Crafters 9709 Lee Highway Fairfax, Virginia 22030 Phone 703-591-5401

Hope this helps! No other info on the back about how the cable was acquired.

Here’s two pics:

http://img425.imageshack.us/img425/2633/1sttransatlanticcable1858sideah4.jpg

http://img393.imageshack.us/img393/7526/1sttransatlanticcable1858topgc2.jpg

P.S. I was aboard her when an earthquake cut a USAF undersea cable and we were

directed to fix it. We did so, quite an interesting operation, one I’ll never forget.

dave777: Actually, I never claimed that the War of 1812 had a victor at all. I stated that the last battle of the War of 1812- which I believe was the Battle of New Orleans- was an American victory. I’ll leave it to others to discuss who won the war…

Thanks, ChickenHead. You picked it up.

I didn’t read all the previous comments thoroughly, but I don’t recall seeing anything regarding withdrawal symptoms. Almost all the pleasure-inducing substances we know about, like alcohol, heroin, methamphetamines, cocaine, etc., have serious and painful withdrawal effects. What about the stimulation of the brain’s pleasure center, is that going to cause serious withdrawal symptoms when it is suddenly, for whatever reason, no longer available? Doctors call it “discontinuation syndrome,” which in my opinion is a euphemism for addiction withdrawal.

Thanks for the link to my atlantic-cable.com site, and nice job with the brief write-up of what was a very complicated story.

I’ll answer a few of the questions that were raised:

Cyrus Field died bankrupt, but not a pauper. He died in his country home where he had lived for many years, and still had possessions to leave to his family. Here are the details of his will:

http://www.atlantic-cable.com/Field/fieldwill.htm

The design of the cables stayed essentially the same from the 1850s until the introduction of amplified telephone cables in the 1950s. The cables used a single insulated copper conductor with iron or steel armoring for protection; the return path was via the sea. Many techniques were used to speed up the transmission, the major breakthrough being “loaded” cable in the early 1900s.

Very few cables were ever picked up from the ocean bed – it just wasn’t economical, as the stress of picking up from several miles down would almost certainly damage the armoring or insulation of the cable. My friend Tom Perera has recently recovered sections of the 1920s cables from Florida to Cuba:

http://www.atlantic-cable.com/Cables/1921KeyWestHavana/index.htm

http://w1tp.com/mcable97.htm

The copper conductor is intact, but the armouring is badly deteriorated. Modern cables use a steel core for strength, with the outer covering being polyethylene or other modern plastics.

Tiffany and Company bought the leftover 1858 cable and sold it as souvenirs; pieces come up on eBay fairly regularly and sell in the $200 -$300 range. The piece mentioned by USNSPARKS above came from the Smithsonian; here’s an article on how they got them:

http://www.atlantic-cable.com/Article/Lanello/index.htm

I’ll be happy to answer any further questions, and there’s a vast amount of information on my site.

Bill Burns

I don’t think this article is explained very well. It starts off talking about a big project, who was in charge, but keeps holding off what this big project is (as DI articles normally do). But then instead of saying something like “They proposed a mammoth cable to stretch the seas yada yada ydaa”, it just jumps straight into “No one knew if it was even possible to send a signal through more than two thousand miles of cable.”. My reaction was “huh? What cable? Is this cable THE project? Is it a phone cable?”.

It starts of explaining how there was a need to communicate better, then jumps right into talking about how the project works, without actually covering WHAT the project was. I found it confusing.

And yet, you managed to figure it out. ALL by yourself. Gold star for you.

I really wished there had been more story to that.. I got to the end wanting to know more!

Umm, First post from me, Hi all :)

John Godfrey Saxe, famous poet of “The Blind Men and the Elephant,” wrote a ballad about this:

Come, listen all unto my song;

It is no silly fable;

‘T is all about the mighty cord

They call the Atlantic Cable.

Bold Cyrus Field he said, says he,

I have a pretty notion

That I can run a telegraph

Across the Atlantic Ocean.

Then all the people laughed, and said,

They’d like to see him do it;

He might get half-seas-over, but

He never could go through it.

To carry out his foolish plan

He never would be able;

He might as well go hang himself

With his Atlantic Cable.

But Cyrus was a valiant man,

A fellow of decision;

And heeded not their mocking words,

Their laughter and derision.

Twice did his bravest efforts fail,

And yet his mind was stable;

He wa’n’t the man to break his heart

Because he broke his cable.

“Once more, my gallant boys!” he cried:

“Three times!–you know the fable,–

(I’ll make it thirty,” muttered he,

“But I will lay the cable!”)

Once more they tried,–hurrah! hurrah!

What means this great commotion?

The Lord be praised! the cable’s laid

Across the Atlantic Ocean!

Loud ring the bells,–for, flashing through

Six hundred leagues of water,

Old Mother England’s benison

Salutes her eldest daughter!

O’er all the land the tidings speed,

And soon, in every nation,

They’ll hear about the cable with

Profoundest admiration!

Now, long live President and Queen;

And long live gallant Cyrus;

And may his courage, faith, and zeal

With emulation fire us;

And may we honor evermore

The manly, bold, and stable;

And tell our sons, to make them brave,

How Cyrus laid the cable!

I’d like to think I’m destined for some sort of greatness because my first name is Cyrus. I mean, Cyrus Field, Cyrus McCormick, Cyrus the Great, and Cyrus MacAvity, how many other Cyri are there in the world? Last names don’t count.

“For example, the bloodiest battle of the War of 1812, while technically an American victory,” is an ambiguous statement. Zack clarified his intent, but it’s not surprising that some had read it the other way.

John Saxe got the story of The Blind Men and the Elephant,from the Buddha, 2500 years before him. All Saxe did was turn it into poem form.

I certainly hope that Mr. Jordan is still writing articles for DI. This is excellent.

Just checking back in.

Back in.

I’m back.