© 2022 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/hunting-for-kobyla/

On a January day in 1964, something remarkable happened: Simon Wiesenthal took the afternoon off. He parked himself at a table on the terrace of Tel Aviv’s Café Roval, soaking up the sunshine as if he wished to bottle it. The friend he’d come to meet was late, but Wiesenthal had no reason to complain.

He was still lounging with his drink and his reading when the loudspeaker crackled to life over the murmur of café chatter. There was a phone call for Mr. Wiesenthal, the disembodied voice announced.

When he rose to take the call (it was the friend; he had to cancel), many of Wiesenthal’s fellow café-goers stood up, too. Then they broke into applause. A spontaneous standing ovation might have startled the average person, but it wasn’t the first time crowds of strangers had risen to their feet in Simon Wiesenthal’s presence. Though when this happened back home in Vienna, it had sometimes been to spit at him.

Neither the love nor the hate fazed the 56-year-old though. Certain occupational hazards were to be expected when you were one of the world’s preeminent Nazi hunters.

Wiesenthal returned to his table to collect his things. When he got there, he found it occupied by three women who, he presumed, had pounced on the prime location. But the women weren’t there for his spot—they were there for him.

“We must apologize for simply sitting down at your table,” the first woman told him in Polish. “But when we heard your name on the loudspeaker we wanted to talk to you. All three of us were at Majdanek. So we thought we should ask you. You must know what happened to Kobyla?”

So much for his day off. Majdanek had been a concentration camp also known as Lublin, and questions like these had recently become the soundtrack of Wiesenthal’s life. After years of working under the radar, he’d recently gained international fame for his role (minimal though it was) in the capture of Adolf Eichmann, one of the Holocaust’s central architects. Wiesenthal’s subsequent book, I Chased Eichmann: A True Story, hadn’t hurt his celebrity status, either. Since the book’s publication, Nazi victims had approached him in droves, begging him to help uncover their former tormentors from the war that had ended almost 20 years prior. Balding and middle-aged, Wiesenthal may not have looked like an international crime fighter. But he had an essential—and surprisingly rare—attribute that suited him to the work: the burning desire to bring the criminals of the Third Reich to justice.

Wiesenthal considered the three women. Their request was familiar, but the name they’d inquired about—Kobyla—was not. He knew that “kobyla” meant “mare” in Polish, but beyond that, he was at a loss.

“Forgive me,” the first woman said. “We always think everybody must know who Kobyla was. We called her that because she was always kicking the women in the camp. Her real name was Hermine Braunsteiner… She was the worst of them all.”

Wiesenthal sat back down as his new tablemates launched into tearful recollections of the prison camp guard who had terrorized the inmates of Majdanek. They told him she threw doomed children onto trucks destined for Majdanek’s gas chambers. They told him she whipped a man so hard that the child hidden in his rucksack cried out. They told him she killed the child on the spot.

“I believe that if they place shards on my eyes when I die, as is our custom, my dead eyes will still see that child’s face,” one of the women said. Everyone’s drinks sat on the table, forgotten.

“From every one of my journeys I return home with new names, the way other people bring back a souvenir,” Wiesenthal told the trio as the chill of the night crept over them. “From this journey it will be the name of Hermine Braunsteiner.”

The most obvious thing to do with a tip about a war criminal who walked free would seem to be to pass it along to the authorities. That option scarcely crossed Wiesenthal’s mind. How times had changed. In the early days of his Nazi-chasing career, as the dust settled on World War II, he’d counted the world’s most powerful nations among his allies. He’d even taken a position with the U.S. War Crimes Office, conducting interviews at displaced persons camps to gather stories—and accusations—from the people there. Within a few years though, his colleagues headed back to the States. When replacements arrived, they seemed much more interested in keeping tabs on the newer, flashier threat—the Soviets—than they were in ferreting out enemies past.

After years spent struggling to keep his offshoot Jewish Documentation Center afloat, Wiesenthal had all but given up on his campaign for justice by 1954. But the 1960 Eichmann capture catapulted Wiesenthal into the spotlight and reinvigorated his quest—as well as his finances.

Most major players in world affairs continued to show no more than a minimal interest in Wiesenthal’s work. But the attention generated by Eichmann’s unmasking—and by his subsequent trial—proved to be a crash course in the power of an unofficial source of leverage: public opinion. Just the previous year, in 1963, Wiesenthal had exposed Karl Silberbauer, the police officer who had arrested Anne Frank and who still held a job in law enforcement. Though Silberbauer hadn’t been a high-ranking official during the war, his arrest made international news, earning time on American network news—despite having to share primetime with the Kennedy assasination. Wiesenthal took the lesson to heart.

Wiesenthal knew people would be repulsed by Braunsteiner’s wartime deeds. If he could fix the eyes of the world on the dramatic and disturbing story of the sadistic camp guard, he believed, he could pressure those in power to take action. He needed to expose Hermine Braunsteiner. But first, he’d have to find her.

Back in his office in the deep freeze of the Viennese winter, Wiesenthal got to work researching his target. He learned that she was a fellow Austrian and that she, like him, had spent time inside concentration camps during the war, just as the women at the café had claimed. Unlike him, crucially, her presence there had been voluntary.

When Hermine Braunsteiner was transferred from Ravensbrück to Majdanek in 1942 to guard its new women’s section, the camp was only a year old. It had been the brainchild of SS chief Heinrich Himmler, who had ordered its construction during a 1941 visit to Lublin. The camp was operational within months, but Himmler’s vision for the site extended far beyond the war. One day, he believed, Majdanek would serve as a clearinghouse where forced laborers could be conscripted to build militarized and industrialized agricultural complexes throughout eastern Poland and the occupied Soviet Union. The result would be a collection of hubs around which ethnic Germans could settle as they spread out across their war-earned lebensraum (living space).

Soviet prisoners of war were the unlucky winners of the initial Majdanek contracting job. Two thousand POWs began construction in the fall of 1941. By February, overwork and exposure to the elements had left nearly every one of them dead. Officials swiftly conscripted Jews from an existing camp in central Lublin to pick up the slack.

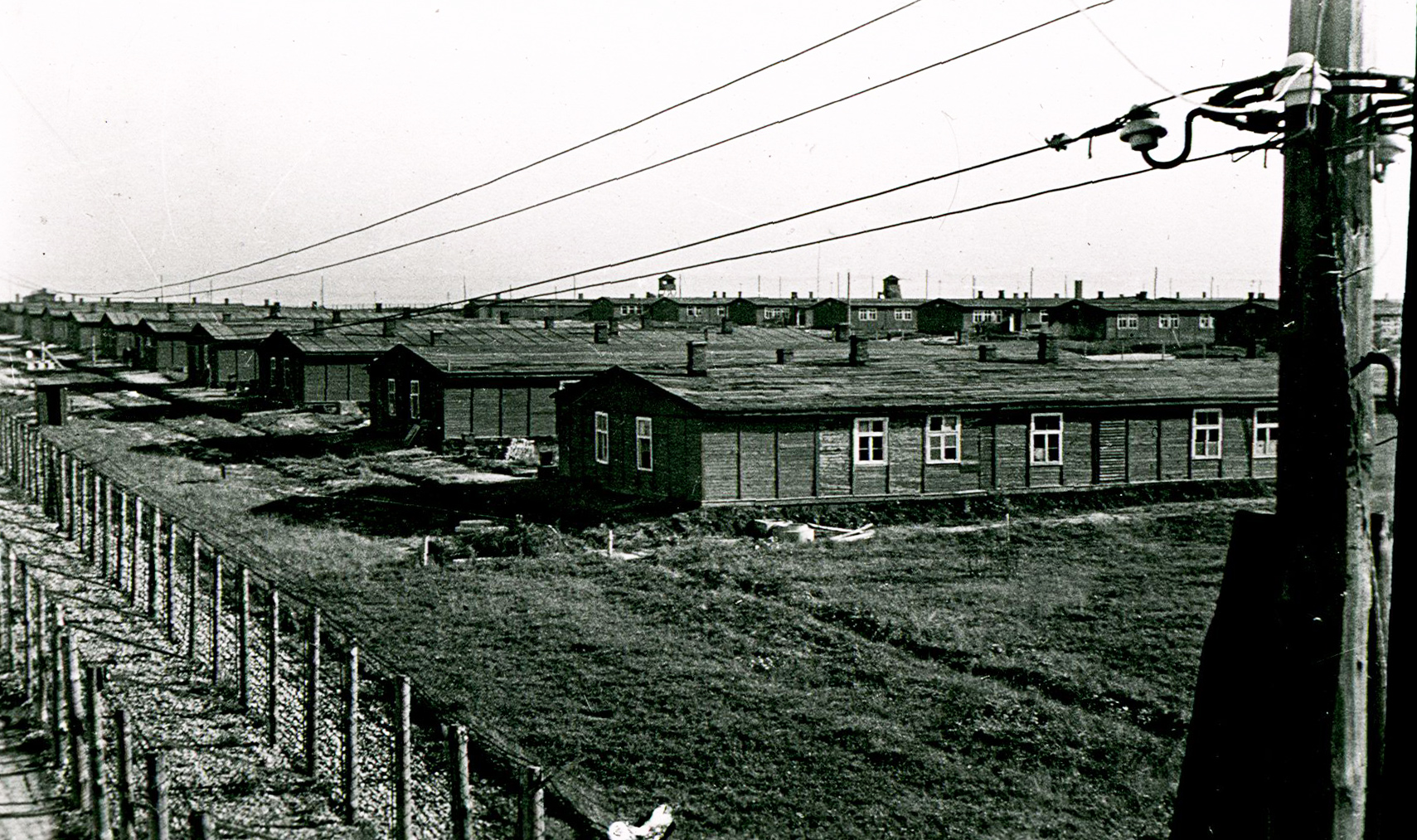

The product of their labor was an impeccably designed hell with a mouthful of an official name: Prisoner of War Camp of the Waffen SS in Lublin. Wiesenthal, who had spent the second half of the war shuttling between camps, recognized the aesthetic. A former architecture student, he had even taken it upon himself to sketch his prisons on scraps of paper during his internment. (The drawings, he figured, would leave behind a visual account of his experience in the likely event that he wouldn’t survive long enough to provide a verbal one.) Now, as he read up on Majdanek, he likely had little trouble picturing its low, wooden barracks set along pin-straight paths, nor the two layers of barbed wire fencing that separated them from the suburban town of Majdan-Tatarski, from which the camp had taken the nickname “Majdanek,” or “little Majdan.” The Majdanek guards’ area had featured a barber’s shop and casino, while the prisoners’ area held sleeping quarters and cremation pyres. Near Field Five, the women and children’s section where Hermine Braunsteiner would likely have spent most of her time, stood three gas chambers.

By the end of its less-than-three-year run, Majdanek proved fatal for approximately 80,000 of the 150,000 people who passed through its walls. Prisoners died from overwork and malnutrition. They died from disease and harsh Polish winters. They died in clouds of poison gas. When the wind blew toward town, the stench of death drifted in with it. The property’s deadliest day came on 03 November 1943, when SS and military men marched some 18,000 people to an area just outside Majdanek’s walls. To drown out the noise, camp administration blared music over the loudspeakers that stood tall throughout the grounds. Thousands of bullets later, all lay dead.

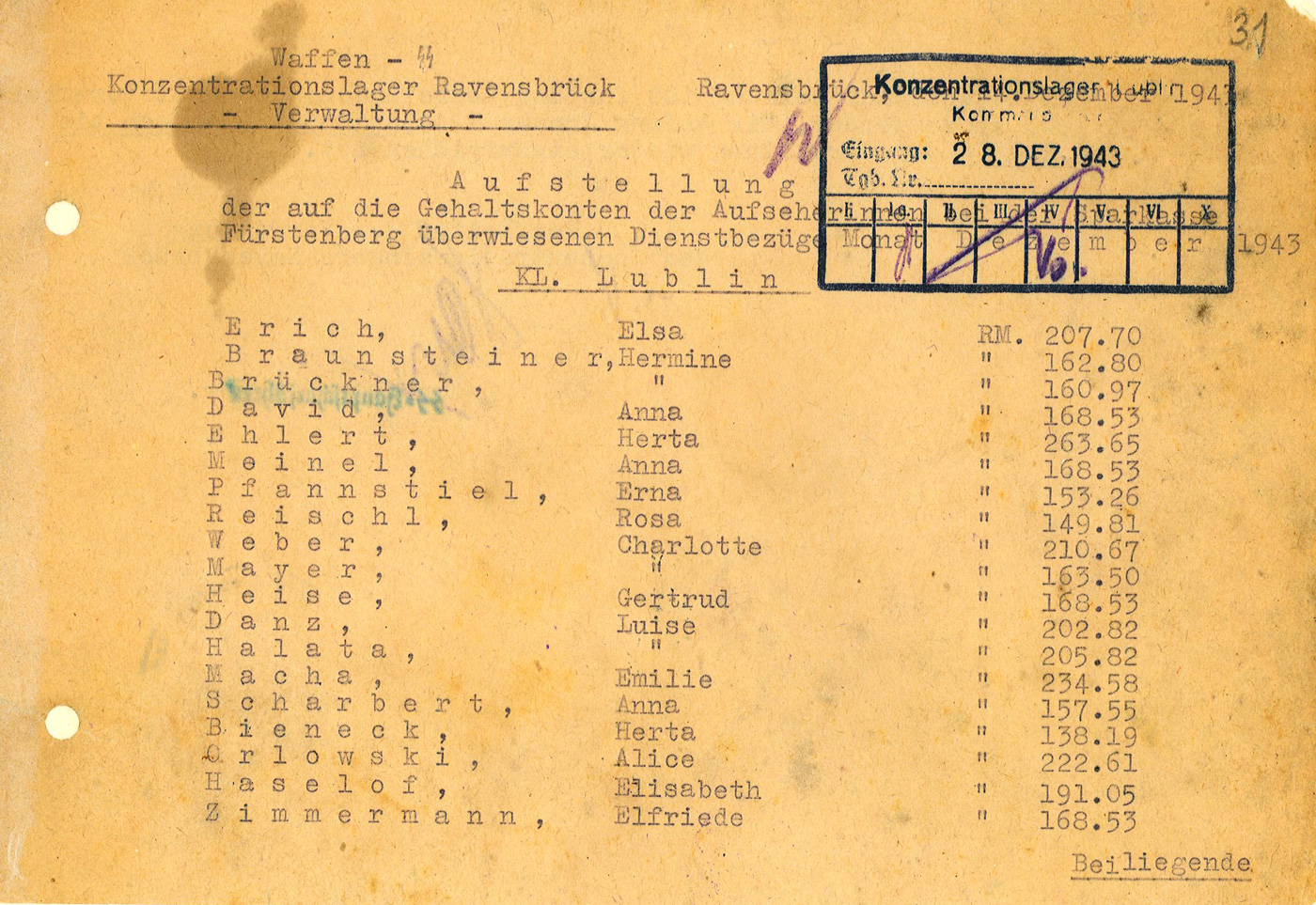

In January 1943, Braunsteiner got good news: She’d been promoted to Assistant Wardress. Perhaps her superiors had been impressed with her cruelty, which had sharpened since her arrival. She had dabbled in her fair share of prisoner abuse in her previous position working as an overseer at Ravensbrück, but at Majdanek, she began to master the profession.

Her assaults took many forms, from lashings with a whip to attacks by the Deutscher Schäferhund (German Shepherd) that often loped along at her side. More than anything though, she became known for her penchant for using her steel-toed boots as a weapon, kicking and trampling Majdanek prisoners who dared to step out of line—or simply encountered her at the wrong moment. Her victims didn’t always survive. Braunsteiner went out of her way, prisoners later claimed, to exert her power and punish those under it. She even inserted herself into the selection process, one witness recalled, during which prisoners were sorted into those who would work and those who would be gassed. While physicians separated the doomed from the spared, Braunsteiner took it upon herself to send additional women to the former group whom she felt, for whatever reason, the physicians had overlooked.

Wiesenthal’s research into Nazi criminals and their killing grounds was never easy reading, but the history of Majdanek hit particularly close to home. With the help of the Polish Underground, Wiesenthal’s wife Cyla had spent much of the war passing as Aryan in Nazi-occupied Europe. Though she survived, she encountered her fair share of close calls. One such near-miss had come when she lived in Lublin, on the day officials had rounded up unregistered residents and sent them to nearby Majdanek. Had Cyla Wiesenthal not been at the back of the line when the registration office closed for the day—and had she not managed to escape later that night—she may well have come face to face with Hermine Braunsteiner.

Braunsteiner had managed to gain her reputation in record time, it seemed, as she was nowhere to be found when Soviet troops took Lublin in the summer of 1944. Eighty of her former Majdanek coworkers were swiftly convicted in the aftermath.

But Braunsteiner hadn’t managed to slip through the cracks entirely. After several more stacks of court records, Braunsteiner’s name finally surfaced on a document from 1948. According to the filings, the ex-guard was eventually arrested in her native Austria. She’d been convicted, too, though the punishment had hardly been stiff. The sentence handed down by an Austrian court was a prison term of just three years. What’s more, she’d only been tried for her abuse of prisoners at Ravensbrück, where she’d spent the early years of the war. No one had testified about Majdanek.

Wiesenthal finally had some crumbs to follow, but they were stale at best. Even if she’d served her full term, he calculated, Braunsteiner would have been out of prison for more than a decade. Where might a convicted Nazi have gone next? He had one guess: home.

Conveniently for a sleuth on a budget, the house Braunsteiner grew up in shared its city with Wiesenthal’s Vienna headquarters. Records at the Vienna registration office showed that she hadn’t lived there since 1946—two full years before her arrest—but Wiesenthal had a hunch that a stroll around her old neighborhood would be worth the trip.

Braunsteiner’s childhood home sat more than 40 kilometers outside the city center. When Wiesenthal arrived, he found himself on a steep residential street near the vineyards that jutted out from the edge of the leafy Vienna Woods. Braunsteiner herself might be long gone from this place, but with luck, he figured, some of those who remained would remember her. He began to knock on doors. Eventually, at 44 Kahlenberger Straße, he found someone who didn’t seem taken aback by the strange man on her doorstep inquiring about a long-gone neighbor. Quite the contrary.

“Of course I knew the girl,” the elderly woman told Wiesenthal, ushering him inside. “What would you like to know about her?”

“I’m interested in Fräulein Braunsteiner because she was on trial,” he told her, not one to beat around the bush.

His bluntness didn’t seem to deter his hostess. “Ah yes, the poor thing,” she said. “I heard about it, of course, and also that she was convicted. There were all kinds of stuff in the papers, about how she was said to have treated the women in the camp. I can’t really believe it of her.”

It was true that Braunsteiner hadn’t seemed destined to be a killer. On the contrary, she’d once dreamed of becoming a nurse. But her family hadn’t been well off, the woman told Wiesenthal, and she was forced to enter the workforce as a teenager while the world continued to limp through the Great Depression.

There was little work to be found in Vienna, so after Hitler’s Anschluss brought Austria under German control in 1938, Baunsteiner decided to try her luck in Berlin. There, in the heart of the rapidly expanding Nazi empire, she found a job at Heinkel Aircraft Works, a manufacturer just outside the city that would soon become known for the bombers it churned out for the German Luftwaffe. The work was steady but the compensation was meager. There were better prospects and pay, the 20-year-old discovered, at a new, women’s-only concentration camp called Ravensbrück that had opened nearby. To a young person short on cash, the gig must have sounded like a dream job. A 1944 newspaper advertisement for Ravensbrück positions promised “good wages and free board, accommodation and clothing.” Braunsteiner secured a position as an overseer. And at that work, she excelled.

As she embraced her new career in the prison camp system, Braunsteiner was rarely seen back in her old Vienna stomping grounds. During the war, her elderly neighbor heard from one of Braunsteiner’s relatives that “Hermine was working as a prison warder in Germany and that she was well.” Later, in 1943, “she turned up once in Vienna,” but “The neighbors at first didn’t recognize her because she was wearing a kind of military uniform.”

The last time the woman had set eyes on Braunsteiner was just after the war. “She came to see me but she didn’t like it in Vienna,” the neighbor explained. “‘There’s nothing to eat here,’ [Braunsteiner] said. ‘I’ll go to my relations in Carinthia.’ And that’s where she was arrested by the police. Perhaps she is back in Carinthia, now that she’s served her sentence. She’s got a lot of relations there.”

Before Wiesenthal rose to leave, he asked for the names of Braunsteiner’s Carinthian relatives. The neighbor readily complied. Wiesenthal now had everything he’d come for.

But in Austria’s southern region of Carinthia, just as in Vienna, Braunsteiner was nowhere to be found. It was time to take a more strategic approach. The search should resume in person, but this time, Wiesenthal would need a surrogate—someone who believed in the work but wouldn’t stand out among the family members of a known Nazi—to go in his place. He knew just the man for the job.

In the afterglow of the Eichmann trial, Wiesenthal had earned plenty of admirers—some of whom wanted to do more than cheer him on. One such would-be volunteer was a strikingly handsome 24-year-old whom Wiesenthal had nicknamed “Apollo.” Now, Wiesenthal summoned the young man back to his office to make good on his word.

With his agent conscripted, Wiesenthal laid out his simple yet risky plan: Apollo would travel to Carinthia, to the village where Braunsteiner’s relatives were said to live. Once there, he would make contact under the pretext of a shared relative and find out all he could. No one was to know his true identity, nor the real reason he was there.

Apollo set off and rented a room in the village. When he found the home belonging to members of Braunsteiner’s extended family, he gathered his courage and knocked on the front door, armed only with a tall tale about common relations in Salzburg. The elderly woman who answered was much less inviting than the one Wiesenthal had met in Vienna. He must be mistaken, she told him—she had no relatives in Salzburg. She moved to close the door.

“Maybe your husband knows something about it,” the amateur spy improvised. Reluctantly, she invited him in. Inside was a young man who seemed more inclined to welcome a stranger. After chatting for a while, the man invited Apollo to dinner.

Over the next few days, Apollo cemented his place as a frequent houseguest, making conversation and joining the family for meals. He was careful to move slowly, lest he show his hand. It wasn’t until his fourth visit that he decided to test the waters and lead the conversation toward Hermine Braunsteiner. He told the assembled group about a fictitious uncle who, Apollo lamented, had been wrongly convicted for his involvement in the war.

“The same thing happened to a woman relative of mine,” replied one of his hosts. “She was sentenced just because as a guard in prison she’d slapped the faces of a few Gypsy women. But happily that’s over. Five years ago she married an American and is now living in Halifax in Canada.” No wonder she’d been so hard to find.

Later, Apollo took a walk with the young acquaintance with whom he’d shared his first meal and decided to press his luck. “Of course you’ll go and see your relative in Canada someday?” he asked casually as they strolled.

“That would be nice, but I’m afraid it would cost a lot of money,” his new friend replied.

“Canada has always been my dream,” Apollo offered quickly, keeping the conversation going. “Wonderfully wild and untouched scenery. Maybe I’ll have saved up enough in a year or two to go there. In that case, I might look up your relative and give her your good wishes.”

In response, his acquaintance offered one last essential insight: “Her name’s Ryan now.”

With Apollo’s vital information in hand, Wiesenthal reached out to an acquaintance in Toronto and recruited him to do some digging on Braunsteiner’s Canadian whereabouts. In just three weeks, the friend sent an update. There was good and bad news, he wrote: He’d found her, but she “no longer lives in Halifax. She has moved to the United States and lives in Maspeth, Queens, N.Y.”

This development put a bit of a wrinkle in Wiesenthal’s plan. In America, Wiesenthal knew that Nazi war criminals slept easy. Not one former Nazi living as a U.S. resident had been extradited by the government in the nearly 20 years since the war’s end. But every new American also had to affirm that they had never, “in the United States or in any other place…been arrested, charged, convicted, fined, or imprisoned for breaking or violating any law.” If Braunsteiner had indeed obtained U.S. citizenship, she had lied on her application to get it by conveniently forgetting to mention her three-year stint in an Austrian jail two decades before.

But how to get to her? Wiesenthal could attempt to contact the American authorities, of course, but their apparent disinterest in the Nazis living among them made that option distinctly unappealing. Instead, he decided, he would turn to his previously tried and true ally: publicity.

Wiesenthal knew his fair share of journalists who could help turn his search into a story. After some consideration, he chose Clyde Farnsworth, a Vienna correspondent for The New York Times who’d recently profiled Wiesenthal for The New York Times Magazine. There was a Nazi living in his paper’s back yard, Wiesenthal told the reporter. Surely, his stateside colleagues would want to take a closer look? Wiesenthal wrote up a detailed account of what he knew and asked Farnsworth to pass it along to the right person in the New York newsroom. Farnsworth obliged.

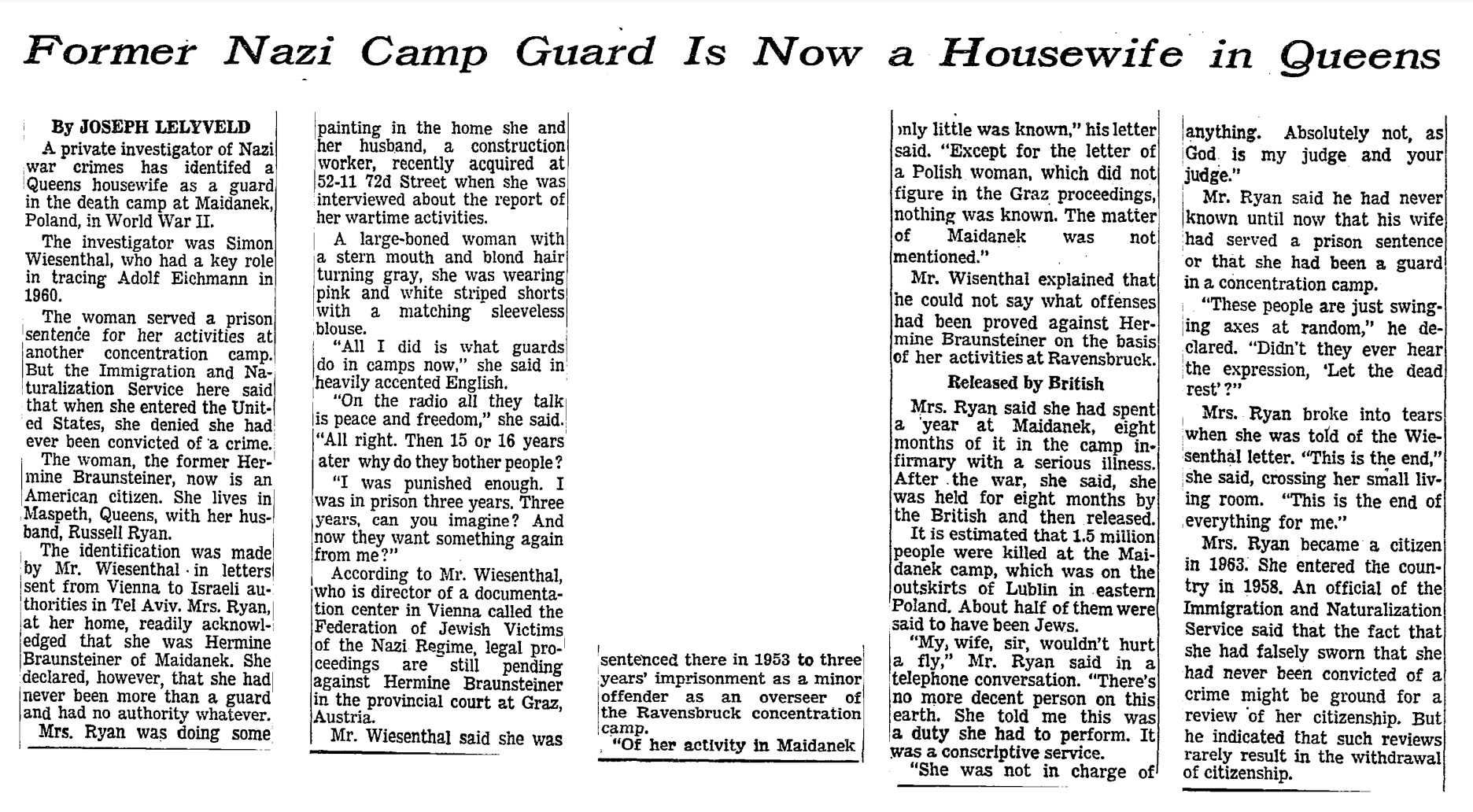

But the assignment failed to reach any of the paper’s top reporters, landing instead on the desk of Joseph Lelyveld, a freshman reporter who had only recently been promoted from trundling back and forth on the subway fetching reports from the Weather Bureau.

It was a Friday morning in June 1964 when Lelyveld set out for the working-class neighborhood of Maspeth, and he had a feeling it was going to be a long day. His orders were as simple as they were daunting: He was to locate one Mrs. Ryan and inquire about her past. As he compiled a list of addresses, the young reporter couldn’t help but notice that there were a lot of Mrs. Ryans living in Maspeth. Having no particular idea where to begin, he simply started ringing doorbells. The first Mrs. Ryan wasn’t the one Lelyveld was looking for, but, to his surprise, she nodded when he asked whether she knew of a different person who shared her name and “who had come fairly recently from Austria, presumably with a German accent.” She pointed the young reporter to 72nd Street.

No doubt amazed by his good luck, Lelyveld set out for the address Mrs. Ryan No. 1 had indicated. There, he found a modest, shingled house with stone steps leading to the front door. He knocked. A woman opened the door. She was tall and middle-aged, her blonde hair coiled in curlers. Clearly, she hadn’t been expecting guests. With a paintbrush clutched in her hand, she looked like any other homemaker taking advantage of a summer day to tackle an overdue DIY project.

“Mrs. Ryan,” Lelyveld said, “I need to ask you about your time in Poland, and the Majdanek camp, during the war.” The surprised housewife stared back at him. Could this harmless-looking woman in pink-and-white-striped shorts really be the sadistic Nazi Wiesenthal’s tip described?

Then she broke. “Oh my God, I knew this would happen,” said the woman, her eyes watering. “You’ve come.”

Inside, the former Nazi concentration camp guard sat with the son of a rabbi in her “tidy living room” and protested the list of accusations from Wiesenthal. She’d been no worse than anyone else, she told Lelyveld, and besides, she argued, “I was punished enough. I was in prison three years. Three years, can you imagine?”

Upon his return to The New York Times building on West 42nd Street that night, Lelyveld’s phone rang. It was Russell Ryan, Hermine’s husband. The middle-aged electrician wasn’t happy. “My wife, sir, wouldn’t hurt a fly,” he told Lelyveld. “There’s no more decent person on this earth.” Mr. Ryan seemed to be among those just now discovering the nature of his wife’s wartime alter ego, but these revelations hadn’t shaken his marital devotion. “These people are just swinging axes at random,” he told Lelyveld. “Didn’t they ever hear the expression, ‘Let the dead rest’?”

Though Russell Ryan didn’t succeed in killing the story, he did manage to give Lelyveld pause. The reporter worried that he hadn’t spent adequate time corroborating Wiesenthal’s claims. The article, originally slated for the front page, ultimately went to print several days later, wedged into a spot on page 10.

Despite its demotion from the front page, Lelyveld’s story made an immediate splash. A Nazi in America? Living peacefully and undetected in the country’s most famous city, no less? No doubt there were many who assumed action would be swift. But it soon became clear that finding Hermine Braunsteiner wasn’t the same thing as catching her. It was time to call in the bureaucrats.

Twenty years and several thousand miles removed from the post-war tribunals overseen by the Allied powers, the U.S. legal code contained no laws that covered Braunsteiner’s actions. Heinous as the allegations might be, the U.S. government had no way to sentence her in an American court for her crimes, which had been committed neither on American soil nor as an American citizen. If Europe wanted to hold the ex-Nazi accountable, that was Europe’s business. The only thing the U.S. could do would be to kick her out of the country, and even that seemingly straightforward matter was sneakily complex. Braunsteiner wasn’t a fugitive or an undocumented alien. No one—save for Simon Wiesenthal—was on the hunt for her. And then there was the minor matter of her American citizenship.

To deport an American Nazi would be an unprecedented move, one that would require the efforts and coordination of two separate federal entities. Having no jurisdiction over the lives of citizens, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service had no hope of shipping Braunsteiner out of the country as long as she could cling to her protected status. It would be necessary, therefore, to deprive her of this legal force field before anything else could be done. The task of removing her citizenship, Herculean in itself, fell to the Department of Justice.

It took four full years before the DOJ decided it had enough evidence, in part thanks to witnesses obtained with help from Simon Wiesenthal, to prove that Braunsteiner had lied on her citizenship papers when she claimed to have no prior arrests. “Had the defendant disclosed the true facts of her conviction, she would have been barred from lawful admission into the United States,” the Justice Department announced in 1968 as the trial kicked off in Brooklyn federal court.

As the court case began, TV camera crews surrounded the Ryans’ house. But the trial itself, which dragged on for years and wasn’t open to the public, sustained little attention. The New York Times published just one article about the proceedings, while Joseph Lelyveld, who first broke the story, pursued a reporting career that took him overseas as a foreign correspondent. Wiesenthal, meanwhile, was busy in Vienna, publishing multiple books and picking fights with high-ranking members of the Austrian government, several of whom he accused of being former members of the SS.

To an outside observer, the case against Braunsteiner may have looked open and shut, but the court battle raged for three years before the defendant made the surprising decision to give up her U.S. citizenship—without admitting guilt to any wrongdoing. It was now 1971. Braunsteiner, no longer a citizen, was finally under the jurisdiction of INS.

The INS attempt to deport the New York Nazi fell to two men. Leading the charge was Vincent Schiano, chief trial attorney and a nearly 20-year INS veteran. Schiano was a “flamboyant dresser” who once sported an “open-necked pink shirt and blue polka dot suit” to a media interview. “He looks more like a Mafia numbers runner,” concluded one reporter, “than the INS’s…top lawyer.” Schiano’s number two, chief investigator Anthony DeVito, was a fiery chain smoker and longtime INS investigator who had been one of the first people to set foot inside a newly liberated Dachau as a member of the Air Force and who’d learned German from his wife, a woman he’d met in the aftermath of the war.

Both Schiano and DeVito recognized how important the case was. If they could convince the judge to rule against Hermine Braunsteiner, they’d be making history—not to mention ridding the country of a war criminal. But Schiano and DeVito’s superiors didn’t seem to share the sense of urgency, and it didn’t take long for the two men to develop a “funny feeling” (as Schiano later put it) that not everyone was as eager to see Braunsteiner deported as they were.

It started with resourcing. As an experienced INS prosecutor, Schiano was accustomed to getting whatever asked for while on the job. This time around, despite the high-profile nature of the case, he found himself barely scraping by. When he arrived at the 14th-floor office that had been provided for him and DeVito in downtown New York City, Schiano found a stuffy, cramped space. It was clearly not a room intended to hold two grown men, let alone serve as headquarters to an anti-Nazi operation. The office also seemed to be missing a telephone. The only way they’d be able to make a call, he realized, would be to use the shared receiver in the corridor or shell out coins for the payphone down the hall.

Undeterred, Schiano and DeVito got to work. And stayed at work, clocking long hours through the weekends hunched over their steel desks. But between the marathon hours spent interviewing witnesses and keeping careful, handwritten notes, the two men continued to wonder whether the rest of the INS was behind them—or even on their side. DeVito’s suspicions were inflamed when a locked file cabinet was broken into overnight. Later, when witnesses traveling from Europe to testify against Braunsteiner arrived in New York, they discovered that the modest stipends they’d been promised were mysteriously tied up. The money went unpaid for weeks while DeVito circled the INS office collecting donations to cover room and board.

Whatever Schiano feared about what was happening behind the scenes at the INS, he knew that once he went to trial, he’d have access to the same weapon Wiesenthal had learned to wield so deftly: public attention. After months of feverish work, the chief attorney was ready to make his case. The litigation against Braunsteiner wasn’t criminal, so she wouldn’t be arrested, let alone shackled at the center of the courtroom. But she would be exposed, and Schiano had reason to believe people would take notice. On 07 February 1972, the trial to deport Hermine Braunsteiner began, and for the first time since she was initially discovered back in 1964, the 53-year-old Nazi concentration camp administrator turned American housewife became major news.

It had been nearly eight years since Braunsteiner first made headlines, and Americans rediscovering her story were confronted with a slew of shocking allegations. Aaron Kaufman, a 71-year-old survivor of eight separate concentration camps, testified that he had seen Braunsteiner whip five women and children to death at Majdanek. Another former inmate claimed to have seen Braunsteiner help load children onto trucks bound for gas chambers. A dentist who had spent more than a year at Majdanek flew from Warsaw to New York to tell the court, just as the three women had told Wiesenthal in Tel Aviv, that Braunsteiner had been so notorious for kicking prisoners that she earned a nickname at camp: Kobyla, or “the mare” in the woman’s native Polish. When she was asked to identify the accused, the 51-year-old witness had no trouble. “The moment I walked in, I recognized her,” she said.

“Easy to say,” Braunsteiner muttered to her husband, seated beside her.

Simon Wiesenthal no doubt kept tabs on the trial, which received copious coverage from The New York Times and other outlets, but never attended a session himself. He had his hands full across the Atlantic, where he continued to make public accusations and pressure governments to prosecute ex-Nazis.

For her part, Braunsteiner continued to present herself as both helpless and without regret. Court sketches show a woman in wide lapels and a flat expression, her mouth sloped down at the edges, eyes narrowed, and eyebrows arched. She did eventually acknowledge that she knew Majdanek was an “extermination camp,” and said she’d been “shocked and appalled” by what went on there. But ultimately, Braunsteiner stood by her lack of culpability. “It was not in my power to do anything,” she insisted. “I was too little.”

Asked whether she had done anything during her time at the camps that she was ashamed of, the defendant answered simply, “No.”

Many who heard about the trial were, unsurprisingly, outraged. Demonstrators gathered on the streets of Queens to protest the fact that Braunsteiner was still free to live her life as a New Yorker. One particularly passionate activist misread the Ryans’ home address and threw a firebomb through the window of a house six blocks away. But public reaction to the courtroom revelations was hardly as unanimous as might have been expected. “Some of these people are real nuts,” said a Maspeth resident. She wasn’t talking about Braunsteiner.

For the most part, Braunsteiner’s alleged secret past didn’t much distress her neighbors. In defending her, they were quick to point out how well she exemplified the character of Maspeth, a safe, middle-class community populated primarily by Poles, Lithuanians, Germans, and Irish. “I find it impossible to believe the accusations against her,” one neighbor told a reporter. “Nobody could have changed that much.” Another summed up the basis for the neighborhood’s shared disbelief more directly: “She’s always working around the house. You never saw such a person for keeping the house clean.”

As time went on, Braunsteiner and her supporters had more and more reason to feel hopeful. The trial, which had at first made headlines, soon stalled. Between the fall of 1972 and spring of 1973, the court held exactly zero sessions. Perhaps in this war of attrition, she could simply run out the clock. But in March, a new bomb dropped, courtesy of the Federal Republic of Germany.

After years of conducting its own investigations, the West German government had concluded that it would very much like to prosecute Braunsteiner itself. So, on 22 March 1973, the Minister of Justice dispatched a 300-page application for extradition. Once the request was submitted, the question of whether the West Germans actually had the right to put Braunsteiner on trial briefly became a matter of some debate. Braunsteiner, of course, was Austrian, not German. What’s more, Majdanek, the camp at which she had spent the most time, had been in Poland, a country which, incidentally, had filed its own extradition request. On this question, Braunsteiner and the West German government were in agreement. Fearing harsher punishment in Poland, she considered German justice the lesser of two evils. Luckily for her, the West German government was firm, and the American government concurred. She had been a supervisor at a German concentration camp, after all, and had acted “in the exercise of German sovereignty.” If she was ordered out of the U.S., Braunsteiner now knew that West Germany would be her destination.

The stakes for the former guard had just gotten a whole lot higher. In response to the extradition request—and for the first time since her discovery—Braunsteiner was placed in custody. She spent the night behind bars at Rikers Island. At her arraignment the next day, she complained that she’d been forced to sleep alongside prostitutes. (Alas, how the prostitutes felt about having to spend the night with an alleged Nazi torturer has been lost to history.)

Sleeping arrangements would soon be the least of Braunsteiner’s worries. Just two months after the West German extradition request, the trial’s chief judge handed down his ruling. On 02 May 1973, the court declared that Hermine Braunsteiner’s life in America was over. Nearly 10 years after being discovered, and almost 30 years after she left Majdanek, Hermine Ryan, née Braunsteiner would return to Europe to answer for what she’d done.

On 08 August 1973, now 53 years old, Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan was led from her cell in the Nassau County Jail to a small holding room at Kennedy International Airport. Holding a Coca-Cola and a box of knitting supplies, she boarded the 6:45 p.m. Lufthansa flight bound for Düsseldorf, West Germany.

She wasn’t going to face the court immediately. As it happened, Braunsteiner was not the only former Majdanek guard the Germans had tracked down, and the authorities had decided to reunite Braunsteiner with her former coworkers in a single trial. Braunsteiner languished in a Cologne jail for two years before charges were filed. When she finally hurried into the Düsseldorf courthouse in 1975 for her mandatory workplace reunion, face hidden behind a newspaper and short hair covered with a white knit cap, she joined five other women and nine men, all removed at least 30 years from their war days. “They looked,” observed a columnist for The New York Times reporting on the trial, “like any row of elderly, modestly dressed passengers on a streetcar.” Of the 15 people on trial, Braunsteiner was the only one who had not made bail, and remained behind bars.

If Wiesenthal had initially been relieved to see Braunsteiner face justice, his impression of the matter soon soured. “What’s going on in Düsseldorf is a circus,” he told one reporter. He had a point. Lawyers for the defense were ruthless, ripping into the witnesses—all Majdanek survivors, many of them elderly—who were called to testify. (One attorney demanded that a former camp inmate who recounted being forced to bring canisters of poisoned gas to the gas chambers be charged as an accomplice.) The trial dragged on this way for years.

Outside of the courtroom though, there was little vitriol. Despite the horror of its subject, the trial was sluggish, bogged down by mundane procedural debates, stalling defense attorneys, and witnesses who had little memory of the things they had seen or done so many years before. German newspapers hardly covered the proceedings, and some politicians went so far as to call for amnesty. For her part, Braunsteiner was again living as a free woman within a year of the trial’s start. She returned each night not to a jail cell but to a small apartment near the courthouse, thanks to the $17,000 (about $51,000 in 2021 dollars) raised for her bail by sympathetic groups, including the New-York-based Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan Foundation.

By 1981, the trial had spanned 474 sessions, featured 254 witnesses, and lasted five and a half years (almost twice as long as the Majdanek camp was in operation), making it the longest and most expensive in German history. During that time, two of Braunsteiner’s defense attorneys had died, as had at least one of her fellow defendants and several witnesses. (Simon Wiesenthal’s 1975 quip that “Death is faster than German justice” seemed prescient.)

In their closing statement, Braunsteiner’s defense attorneys focused on technicalities rather than their client’s actual innocence. Her extradition, they argued, had been illegal. Plus, she was an Austrian, not a West German, so how could she be held accountable to a foreign government? Furthermore, they contested, she’d already served time for her alleged misdeeds back in Austria in the aftermath of the war. With that, the trial came, at long last, to an end.

On 30 June 1981, the ex-guard known for her whip and her steel-toed boots filed into the courtroom for the final time. It had been almost a decade since she had boarded the plane bound for West Germany and more than 15 years since a young Joseph Lelyveld—now just five years away from winning a Pulitzer Prize—had knocked on her front door in Queens. It had been nearly 20 years since Simon Wiesenthal had tried to take the afternoon off at a café in Tel Aviv. Braunsteiner was now 61 years old, her hair steel gray. Her husband Russell, who had followed her to West Germany in 1977, sat in the visitors’ gallery.

With him were a smattering of other onlookers, some friendly, some hostile. It was hardly a large or rambunctious crowd. As the assembled spectators peered down into the courtroom, they could see only the backs of the defendants who sat quietly and faced forward as they awaited their fate. An eerie calm hung over the room. When the judge entered the room, one journalist noted, he was the only one who looked uneasy.

All eyes fixed on him as he read out the verdict. Hermine Braunsteiner, who had been accused of playing a role in the deaths of more than 1,000 women and children, was guilty of exactly two of them, he announced. After so much time, it was all the evidence could prove. She would pay by spending the remainder of her life in prison. Of the nine remaining defendants (seven of whom were found guilty), she alone received a life sentence.”Scandal!” shouted one man in the public gallery, outraged by the leniency. “You have learned nothing, absolutely nothing!” An emotional prosecutor could muster only shock. “Surprising,” he said. “Very surprising.”

Those on the other side expressed equal distaste. “American Jews demanded these trials, and this is what happened,” Russell Ryan concluded bitterly.

Braunsteiner’s second stint as a convict lasted less than 15 years, less time than elapsed between Joseph Lelyveld’s fateful story and the German trial’s conclusion. Released due to ill health caused by her diabetes in 1996, she spent her final three years in a German nursing home alongside her ever-loyal husband. She died in 1999 at age 79.

Rather than opening the floodgates for war crimes extradition from the U.S., Hermine Braunsteiner proved to be one of the few ex-Nazis—and the only female one—ever removed from the country. Fewer than 70 known Nazis have been deported, extradited, or left voluntarily since. How many more have lived their lives undetected is less clear.

After Braunsteiner’s extradition case wrapped up, both Schiano, the chief INS attorney, and DeVito, the chief investigator, publicly accused the INS of dragging its feet and avoiding Nazi prosecutions. Both men left the agency, in 1972 and 1973, respectively. In 1974, Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman publicly accused the federal government of neglecting the search for Nazis in the U.S., and in 1977, DeVito and Schiano were finally called to testify before Congress. The Office of Special Investigations, the government’s first official Nazi hunting agency, wasn’t established until 1981.

As for the man who brought Hermine Braunsteiner her unwanted fame, Simon Wiesenthal continued to make the headlines—and the enemies that came with them—until his retirement in 2001. He was by then 92 years old. “I have survived them all,” he said of the Nazis he’d spent half a century chasing. “If there were any left, they’d be too old and weak to stand trial today. My work is done.”

© 2022 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/hunting-for-kobyla/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://www.damninteresting.com/donate ?

Uno

DI, as always! Lest we forget . . . . our simple task is but to remember, that it never happen again.

Fascinating story, as always from DI, but it does bring home to me how a huge number of these inhuman criminals escaped punishment and went on to lead normal lives after the war. Which is horrific in itself.

Always fantastic to come on to the website and find another story has been published! Damn interesting indeed, and very well-written!

Nice to read something with a connection to my home city, even though the topic is rather grim. Also brings back memories of my visit to Majdanek in 2020, I didn’t know about Braunsteiner back then, actually.

One minor comment though: 40 km from the city center would be *far* beyond Vienna city limits, for that adress in Kahlenberger Straße it’s more like 5-6 km, maybe revisit this number again.

I got a sense of unease from reading this. It is worrisome that in the sixties and seventies when the horrors of the holocausts were fresh in the minds of the population very little was being done to bring the perpetrators to justice. Seems we didn’t learn the right lessons then and today looks worse.

First, E. Schulte is spot on.

Second, I have read extensively about the Holocaust, and this is the first time that I have heard of Braunsteiner. How could she have escaped my attention?