© 2006 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/the-timber-terror/

In the late 1930s, the dark cloud of war was lurking on the horizon in Europe. Even as the United Kingdom and France employed diplomats to appease Hitler with compromises, each country also began reinforcing its military in anticipation of hostilities. Among other preparations, Britain’s air force ramped up production of its state-of-the-art bombers. These large aircraft were well-armored and capable of delivering a brutal amount of destruction; but the four-engine steel/aluminum planes were slow and ungainly, leaving them highly vulnerable to fighter planes and anti-aircraft weaponry.

Despite shortages in the metal supply, the Royal Air Force (RAF) made plans to broaden their air fleet to include a new variety of bomber which was somewhat smaller and faster. In 1936 the RAF commissioned several companies to submit designs for such a plane, and a civilian outfit called De Havilland responded with a highly unorthodox concept: a bomber constructed almost entirely out of plywood. Initially the British Air Ministry scoffed at the idea, and suggested that the airplane company instead use its resources to construct wings for existing bomber designs. But the people at De Havilland were convinced that their unconventional idea had some merit.

The aircraft designers originally conceived of a wooden airframe armed with several gun turrets and a six-man crew, all propelled by a pair of Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. A series of calculations soon indicated that such a plane wouldn’t be particularly fast given its heavy weight, so the engineers discussed adding two additional engines to bring it up to the speed of existing bombers. After some consideration, the original thinkers at De Havilland concluded that the best way to defend an aircraft wasn’t with bristling machine guns, but by making it so fast that nothing in the sky could catch it.

The approach seemed reasonable, so the design team continued to tinker with their wooden aircraft concept— though it still hadn’t received the blessing of the RAF. They discarded the gun turrets and four of the crew positions, a reduction which significantly decreased the estimated weight. They also paid close attention to the aerodynamics of the craft, aiming for a skin as slippery as that of a fighter plane. With its pair of supercharged Merlin engines, the lightweight plywood design was estimated to have a top speed of 400 miles per hour with a full bomb load, easily outpacing Germany’s fastest fighters.

The RAF continued to be apprehensive in spite of the impressive specs; a lightly-armed wooden bomber was profoundly contrary to the thinking of the time. Fortunately De Havilland had an ally in the British Air Ministry, a man named Sir Wilfrid Freeman. Freeman had been friends with the De Havilland family since World War I, and he saw the potential in the new design. At his coaxing, the Air Ministry finally authorized construction of the prototype, largely due to Freeman’s observation that the wooden airplane would not sap the country’s already bedraggled metal supplies.

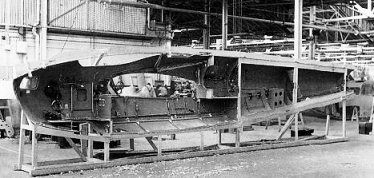

After some setbacks due to equipment shortages and German bombings of the De Havilland buildings, the Mosquito prototype was transported to the town of Hatfield for a test flight on 25 November 1940. Its final construction was heat-formed plywood over a wooden frame, with sections glued and screwed for extra strength. It employed Ecuadorean balsawood sandwiched with Canadian birch, a particularly strong and lightweight grade of plywood. Metal was used in only a few parts, including the engine housings and some control surfaces. The wooden sections were covered in fabric and the prototype was painted bright yellow to discourage British anti-aircraft crews from firing upon the top-secret airplane. A series of test flights over the following months confirmed that the Mosquito was an extremely agile and swift machine, executing impressive acrobatics and reaching speeds up to 392 miles per hour. Further testing also discovered that the aircraft could easily heft four times the load it had been designed for.

Official attitudes towards the Mosquito quickly changed after observing the prototype in action. The RAF ordered a number of the aircraft in several configurations, including bombers, heavy fighters, and photo reconnaissance. De Havilland enlisted the assistance of carpenters, piano makers, cabinet builders, and other woodworkers who had been previously unable to make an appreciable contribution to the war effort. Sub-assemblies were constructed in places such as furniture factories, then sent to the De Havilland plant for final assembly in large concrete moulds. To speed production, engineers developed a technique where the glue was rapidly dried with the assistance of microwaves.

The unlikely wooden aircraft quickly established itself as one of the most useful planes in the Royal Air Force. The bomber varieties could deliver a payload comparable to that of the flying fortresses, while consuming less fuel, putting fewer lives in danger, and cruising at about twice the speed of the larger bombers. The Mosquito was also useful for low-altitude runs, where squadrons of Mosquitos flying at rooftop heights dropped their ordnance with precision, departing at full speed with German interceptors in hopeless pursuit.

The heavy-fighter version proved to be fast and deadly, flying bomber escorts and shooting down almost 500 of Germany’s V-1 rockets. Some fighters were given a 57mm cannon and rockets for sinking U-boats at sea. A night-fighter variant was equipped with Britain’s new top-secret radar set, allowing the Mosquito to find its prey in the darkness.

When British intelligence learned that the commander of the German Luftwaffe Hermann Göring was due to address a Nazi parade in Berlin on 31 January 1943, they devised a plan to demoralize the enemy. Göring had long boasted that Germany’s capital was safe from Allied bombers, but on that morning the lie was given to his claims when a mess of bombs was delivered to the rally by a gaggle of Mosquitos. Another squadron of Mosquitos went on to disrupt a second rally in Berlin on the same afternoon. On a separate occasion, British Mosquito pilots conducted very-low altitude bombing of Gestapo headquarters, destroying important records and freeing numerous prisoners. Due to daring raids such as these, the Mosquito came to be affectionately known by the nicknames “Wooden Wonder” and “Timber Terror.” Even Hermann Göring himself held the Mosquito in high regard:

“In 1940 I could at least fly as far as Glasgow in most of my aircraft, but not now! It makes me furious when I see the Mosquito. I turn green and yellow with envy. The British, who can afford aluminium better than we can, knock together a beautiful wooden aircraft that every piano factory over there is building, and they give it a speed which they have now increased yet again. What do you make of that?”

Perhaps the most daring Mosquito raid was that of Operation Jericho, a bold and somewhat desperate undertaking meant to free condemned prisoners of war. On 18 February 1944, a flight group consisting of nineteen Mosquito bombers along with fighter escorts dashed at top speed over Nazi-occupied France towards Amiens Prison. Allied forces had learned that one hundred and twenty captured members of the French Resistance were scheduled to be executed there the following day, and an audacious plan was hatched in the hopes that some of the prison’s 717 prisoners might escape.

Just after noon the first wave of Mosquitos roared into view over the prison, and pilot Maxie Sparks started a dive through a storm of anti-aircraft fire. Their crate weathered a number of rounds from the defenders before it let loose its first bomb, which struck the prison wall as planned. The Mosquito came around for a second pass, and navigator Cecil Dunlop executed another expert drop which blew a second, even bigger hole in the outer wall. Amidst the smoke and chaos, many prisoners fled from the prison as the second wave of Mosquitos arrived and targeted the Nazi guard quarters. Although 102 prisoners were killed, 258 managed to escape, including seventy-nine of those who had been scheduled for execution. Some historians have speculated that the D-Day landings which followed a few months later might not have been successful without the help of the French Resistance prisoners which were freed from Amiens.

For several years the inexpensive Mosquito bombers dominated the skies in terms of speed and versatility. Eventually a handful of German fighter planes were developed which were slightly faster than the Mosquitos, but most of the time the wooden bombers were already on their way home by the time the interceptors arrived, and the small speed advantage was insufficient to close the gap in a reasonable time. Towards the end of the war Germany finally developed a jet-powered plane with enough speed to catch the Timber Terror, but their introduction came too late to make a significant impact. The Mosquito also played a small role in the Pacific theater, but its use was limited because its wood-and-glue construction proved to be problematic in the humid climate. Some planes quite literally came unglued due to the heat and moisture, a problem which may have led to a few crashes.

By the time the war was over, not only had the Mosquito proven itself to be capable, but in many ways extraordinary. These aircraft— primarily built by carpenters using commonplace materials— flew over 28,000 missions for Bomber Command, and only 193 of them were lost in the duration of the war. A Mosquito named F for Freddie held the record for the most bombing runs by a single aircraft in World War 2, having executed 213 sorties. The last Mosquito was built in 1950, and the Wooden Wonder remained the fastest aircraft in Bomber Command until 1951.

Unfortunately the wood construction has not weathered the years as well as it weathered the war; only about thirty preserved specimens remain, and none are airworthy. The original prototype survived, however, and is currently undergoing complete restoration in the De Havilland Aircraft Heritage Centre in Hertfordshire, United Kingdom.

© 2006 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/the-timber-terror/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://www.damninteresting.com/donate ?

First!

That useless comment aside, I’d have to label this article as one of the most interesting.

Articles on the war always catch my eye- I find them the most interesting.

Wow! I wish that they taught engineering feats such as this back in High school history. We learned so much about the politics behind the war but rarely touched on the incredible ideas that came fourth as a result of wars. Perhaps it would inspire even more kids of the future generations to think outside of the box. Just like the engineers of De Havilland. They could serve pie in class too! Oh wait, some states have made laws against serving sweets in class cause a few kids are not taught how to eat a proper diet. That’s frustrating! Why can the few always mess things up for the many!? Sorry, tangent; Damn interesting article!

Try turning this into a battle about religion and evolution.

Great article by the way.

The planes evolved…?

As always, DI…

An unexpected side effect to having a plane made mostly of wood is that radar passes right through it. Since it contain very little metal and radio reflective materials, essentially just the engines and key instrumentation, it had/has a very small radar cross-section for it’s size. Someone could consider it one of the first “stealthy” planes (next to the German Horten Ho 229 ).

Great read. I had absoluttely no idea that successful wooden war planes exsisted.

Great story, Alan! This type of thing is DI at its finest.

The war ended in 1945, yet they kept building them until 1950? Interesting.

I wonder why all the best stuff in the world doesn’t stay around that long (the mosquito, Firefly, the SR-71, Cupid, Strange Luck, etc….) yet the lemons tend to persist (Edsels, soap operas…)?

Cepheid: are you an amateur astronomer by any chance?

Man said: “Try turning this into a battle about religion and evolution.

Great article by the way.”

Evolution is a farce! :-)

etonalife said: “The planes evolved…?”

Still bitter? Well, if it makes you *feel* any better, I actually believe in the evolution of the airplane. The design of airplanes was indisputably directed over time by intelligent engineers. How else would one explain their progressive development into *only* safer, faster and more feature-rich machinery? The evolution of the airplane is indisputable because the entirety of its inception and development has taken place within the limits of human observability. Otherwise, the cone of uncertainty would come into play and human-error would most certainly appear.

Nevertheless, the inferiority of the airplane (compared to biological systems) can be illustrated by it’s apparent lack of self-replication, but with research into nano-technology underway, who knows what the 767 will be 65 million years from now? I’ll refrain from interjecting that principles of flight have been observed in biological entities ’cause that could start some kind of flame-war and get people all sore with me. Oh, wait, did I mention that?

Denial from batteries who will not admit the sum of 1 and 1 would seem appropos at this juncture… :-) Yes, I know I’m being antagonistic but be gracious; ’tis all tongue-in-cheek–this time!

PLEASE DO NOT TURN THIS INTO ANOTHER ARGUEMENT ABOUT EVOLUTION … CAN WE STICK WITH THE BARE FACTS AND TALK ABOUT THE STORY!!!

anyway…DI article…

Some how i dont think wooden planes would work today especially as modern planes go a far bit faster.

:-D

I agree no more talk of creation, religion, evolution or anything else unrelated to the article.

I am very sorry I brought it up, now lets never speak of this again.

The SR-71 was put down because it cost a lot to build and its maintenance was incredibly expensive. Even though it was the best, there was really no reason to keep it.

Actually, there’s no reason to keep much of the current arsenal of planes in the air force inventory. Air power is a thing of the past.

God created tree and these evolved into mosquitos.

And the airplane did not evolve from the Wright Bros contraption…

http://www.idsia.ch/~juergen/planetruth.html

@Drakvil

Messerschmidt ME-109´s were in use and production till 1965 in Spain.

PS That´s why, when they made the movie “Battle of Britain” (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0064072/), they had more ME-109´s flying then Spit´s and Hurricanes. They just had a bunchload at their disposal with qualified (Spanish) pilots. Here is more on the Spanis ME-109:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hispano_Aviacion_Ha_1112

Here an example of a bizar version of the ME-109 build after the war from old spares by the Czechs (note the user):

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avia_S-199

Kuz_Sam said: “anyway…DI article…

Some how i dont think wooden planes would work today especially as modern planes go a far bit faster.

:-D”

Lol. Good luck mounting a turbofan on a wooden wing :D

Some how i dont think wooden planes would work today especially as modern planes go a far bit faster.”

Wasn’t there a spacecraft that used a wooden heatshield? I don’t know the details but someone else might have a better idea.

@Xiphias

Not quite. I think you´re confused with the “lifting body” aircraft. They look quite “spacey” and are made of plywood.

See:

http://www.nasa.gov/centers/dryden/news/FactSheets/FS-011-DFRC.html

Look for the: M2-F1

Cepheid the Spectre said:

“an unexpected side effect to having a plane made mostly of wood is that radar passes right through it.”

Great point! This plane is simply…damn interesting. Speaking of wooden planes, the Hughes H-4 “Hercules” (a.k.a. “Spruce Goose”) was also built out of wood in order to conserve metal for the war effort. Is there anything lumber can’t do?

Thanks for the DI article Alan. Story that deal with aviation are always great, at least to me. It sure is a great way to start a Sunday too!

Cepheid the Spectre said: “An unexpected side effect to having a plane made mostly of wood is that radar passes right through it. Since it contain very little metal and radio reflective materials, essentially just the engines and key instrumentation, it had/has a very small radar cross-section for it’s size. Someone could consider it one of the first “stealthy” planes (next to the German Horten Ho 229 ).”

That might be a consideration today, but in the 1940’s precious few war craft of any sort were equipped with radar.

Great job, Alan. This is the kind of article that keeps me coming back to DI.

It’s so weird. I’ve never heard of a engine powered machine being wooden. I’ve never thought about it at all. When you say, why not make a plane out of wood instead of metal, it sounds like the plane would be much weaker because wood is weaker. Yet that’s far from the truth. That’s friggin awesome!

just_dave said: “That might be a consideration today, but in the 1940’s precious few war craft of any sort were equipped with radar.

Great job, Alan. This is the kind of article that keeps me coming back to DI.”

There were ground based installations.

CanInternet said: “God created tree and these evolved into mosquitos.”

Funny!

CanInternet said: “And the airplane did not evolve from the Wright Bros contraption…

http://www.idsia.ch/~juergen/planetruth.html“

Of course it did. There were evolutionary predecessors to the Wright brothers as well as successors.

Zaphod2016 said: “… Great point! This plane is simply…damn interesting. Speaking of wooden planes, the Hughes H-4 “Hercules” (a.k.a. “Spruce Goose”) was also built out of wood in order to conserve metal for the war effort. Is there anything lumber can’t do?”

Well, you could not build a large suspension bridge from natural fibers. Balsa is a remarkable material. It is (I believe) the strongest wood when weight is considered. It is renewable and amazingly fast growing.

Shandooga said: “Still bitter? Well, if it makes you *feel* any better, I actually believe in the evolution of the airplane. The design of airplanes was indisputably directed over time by intelligent engineers. How else would one explain their progressive development into *only* safer, faster and more feature-rich machinery? The evolution of the airplane is indisputable because the entirety of its inception and development has taken place within the limits of human observability. Otherwise, the cone of uncertainty would come into play and human-error would most certainly appear.

…”

AHA! So you admit that an intelligent designer could use evolution as a tool in the design of something?

Great article, on the best site on the web, made me proud to be Brittish! witch is something that dosent happen very often these days. keep up the good work.

Sure wish some of the people commenting on these stories would evolve.

Damn Interesting article. Keep it up!

Great post. (And sorry so many of my fellow Christians have a pickle up their arse when it comes to basic science. I thought the cat article was fantastic too.)

Not only is the article interesting, but parts of it could make other DI stories, as well (the Berlin rallies and Operation Jericho).

CanInternet said: “@Xiphias

Not quite. I think you´re confused with the “lifting body” aircraft. They look quite “spacey” and are made of plywood.

Not quite, although weren’t some of the flying wings made out of wood too?

I did a bit of digging around and this is what I was refering too: http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg14619738.300-space-oddities.html

Didoka said: “It’s so weird. I’ve never heard of a engine powered machine being wooden. I’ve never thought about it at all.”

There are a lot of them about.

Damn and in those days I used to read the New Scientist. Must have missed that article on the wooden heatshield. Thanks for the link.

Anyway, heatshields work by burning off their outer layer. The thicker the layer the longer it can burn and protect. It is the chared layer that gives the protection against the generated heat. This goes for conventional heatshields and not the ceramic tiles on the space shuttle. That´s another story.

Wow, damn! What an interesting story! This quality article is a prime example of why I visit this site…just incredible! Keep up the good work fellas. ;-)

sulkykid said: “AHA! So you admit that an intelligent designer could use evolution as a tool in the design of something?”

Stop it.

Fascinating article, by the way. The only wooden plane I was well aware of was the Spruce Moose.

HunterKiller_ said: “Great read. I had absoluttely no idea that successful wooden war planes exsisted.”

I don’t get it. Surely you guys know pretty much all planes (successful or not) were made of wood and fabric up until the late 1920’s?

What might be more surprising is that DeHavilland went on to make some of the earliest jet fighters out of wood also (the Vampire first flew in 1943)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Havilland_Vampire

sulkykid said: “AHA! So you admit that an intelligent designer could use evolution as a tool in the design of something?”

Shandooga, for the love of God, please, please let this comment go. That goes for anyone else who’s thinkin’ ’bout startin’ somethin’!!

That aside, I thought it was incredibly DI. I always enjoy articles such as these that have a bounty of information that goes on far longer than I expect. I never knew anything like that type of plane ever existed.

I wonder why the Nazis never developed this type of plane in retaliation? From the quote it seemed as though there wouldn’t have been any confusions as to what these new planes were made of. Also, did America take any part in making planes like these? Or was it simply a matter of transportation across the humid ocean? Did the weather over in Europe ever affect the planes? I’m sure more questions will come soon.

Lookin’ forward to the next one!

Man said: “I agree no more talk of creation, religion, evolution or anything else unrelated to the article.

I am very sorry I brought it up, now lets never speak of this again.”

Good idea; that’ll make the issue go away.

sulkykid said: “AHA! So you admit that an intelligent designer could use evolution as a tool in the design of something?”

Sulkykid: No, that’s not what I meant but, before I explain, see quote from Misfit below…

Misfit says: Shandooga, for the love of God, please, please let this comment go. That goes for anyone else who’s thinkin’ ’bout startin’ somethin’!!

Since I was asked nicely and I don’t really want to ruin anyone’s experience on the site (which I also enjoy) I will invite you (and anyone else who so-desires) to continue the discussion privately via email. shandooga@hotmail.com

Wow, the evolving understanding of aerodynamics sure have lead to some intelligently designed airplanes. It’s great to see people take various innovations out of their original box (idea/purpose) and apply them to different technologies or in different ways. With warplanes and dog fights it’s very much survival of the fittest — if your plane is too slow you’re dead!

Hi All!! I just registered because i love this site and find the articles damn interesting – this article included. But the real reason i registered is to say that i think there should be an article written about the attempts to be the first to post a reply… how old are you? Why do you do this? What dives your little brain to think it’s cool to post a first response on a website?!?! Grow up and concentrate on writing better comments than this one!!!

Great article. Took me back a bit as I used to work at Salisbury Hall, now the Mosquito Aircraft Museum.

The design team worked there, built the prototype there and it’s a fitting end to see it end up there.

The place has expanded quite a bit since though and when I last visited, you could climb into various planes and get a idea what a pilot’s eye view would have been, so I thoroughly recommend it.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosquito_Aircraft_Museum

outsidersdream said: “Wow, the evolving understanding of aerodynamics sure have lead to some intelligently designed airplanes. It’s great to see people take various innovations out of their original box (idea/purpose) and apply them to different technologies or in different ways. With warplanes and dog fights it’s very much survival of the fittest — if your plane is too slow you’re dead!”

LOL!!!! You are bad.

Weren’t all airplanes originally made out of wood and bits of metal?

Anyone here read zzz.com.ru?

Shandooga said: “Since I was asked nicely and I don’t really want to ruin anyone’s experience on the site (which I also enjoy) I will invite you (and anyone else who so-desires) to continue the discussion privately via email. shandooga@hotmail.com“

Thank you, Shandooga. The gesture is quite appreciated.

Everebody is so surpised by wooden planes. That surprises me. Never heard of World War I?

The Boeing P-26A was the first all metal fighter of the US (link).

The DC 2 was the first all metal passenger plane, one is still flying and in the collection of the dutch airmuseum called “De Uiver” (link).

The Junkers J.L. 6 was probably the first plane with the fuselage, wings, and skin all constructed of metal.

(link)

The DC2 is called “De Uiver”, the museum is called “Aviodrome”

I wasn´t quite celar on that.

They do once in a while short flights with De Uiver for members of the museum.

CanInternet said: “Everebody is so surpised by wooden planes. That surprises me. Never heard of World War I?”

The surprise for me is not that a wooden plan existed, but that it far outperformed most of its metal counterparts (even though wood planes were considered obsolete). This story represents unconventional thinking at its finest.

outsidersdream said: “With warplanes and dog fights it’s very much survival of the fittest”

I thought evolution was taboo now.

Good article.

Oh wow… okay so far I can recall three topics of MAJOR debate over the time since I’ve been a member.

Numero Uno: El Presidente

Numero Dos: Evolution

and number three: People who enjoy being first to comment..

Bewildered said: “Hi All!! I just registered because i love this site and find the articles damn interesting – this article included. But the real reason i registered is to say that i think there should be an article written about the attempts to be the first to post a reply… how old are you? Why do you do this? What dives your little brain to think it’s cool to post a first response on a website?!?! Grow up and concentrate on writing better comments than this one!!!”

Your admiration for this site is touching; however, if you’ve been following the discussions as closely as you’ve implied, you’d realize that comments like these are what can REALLY get us off track, and as well, you joined here for the SOLE PURPOSE of doing so. becoming a member just to chastise those who rejoice in a pleasure as simple (and completely HARMLESS, I might add) as being the first to comment? Looks like you need to re-examine who’s being immature here. Next time, follow your own advice and talk about the articles you love.

As for anyone who’s been tossing and turning and losing sleep over my questions earlier, I’ve found out that America had a play in this after all. Here’s a quote from commonwealthplywood.com:

“In 1941, the Mosquito was the fastest operational military aircraft. Colonel Elliot Roosevelt of the U.S., after flying a Mosquito, wanted to trade a squadron of his P-38 Lockheed Lightning fighters for a squadron of Mosquitos. The Russians wanted to build a factory to manufacture the bombers. On several occasions it was proposed by the Americans that Mosquitos be swapped for either P-38 Lightnings or the P-41 Mustangs. Air Marshall Freeman vetoed these swaps because of demand for the aircraft by the RAF and because he felt America possessed no plane worth swapping for the Mosquito.”

(Why he couldn’t just replicate the technology involved himself, I do not yet know)

Oh, final word of parting, I would like to express a word of sincere thanks to all that have kept their distance from doom death and destruction debating here.

Oh, and also,

WELCOME TO THE DI COMMENT SECTION, BEWILDERED!

Awkward welcoming party coming from me, I know. Umm………… where’s Floj with his offerings of pie when you need him?

Werent some of the olden day bi-planes made out of paper?

What might be more surprising is that DeHavilland went on to make some of the earliest jet fighters out of wood also (the Vampire first flew in 1943)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Havilland_Vampire“

I didn’t realise the vampire was made of wood. Do you happen to know if the comet was as well?

Xiphias said: “I didn’t realise the vampire was made of wood. Do you happen to know if the comet was as well?”

No, I don’t believe it was. But maybe if it was the windows wouldn’t have had a tendency to explode. :) It’s strange to think how the world of civil aviation might be so different now if it wasn’t for that small design flaw.

In many ways, wood is superior to aluminum as an aircraft material – strength to weight can be better, and you don’t have aluminum’s fatigue problems. Wood’s major disadvantages are its inconsistancy (no 2 trees grow the same) and rotting. Wooden planes are still being built and flown by homebuilders.

Why didn’t Germany produce a simular plane? The Germans were so impressed by their early dive-bombers that al bombers were required to be capable of dive-bombing. Dive-bombers need to be strong enough stay together coming out of a vertical dive, so tend to be heavily built and slow. This requirement wasn’t changed until it was a bit late to get new designs into production

A very big mostly wood build airplane was the “Gigant ME-323”. Originaly a glider, but later “improved” with engines and take-off assist rockets.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Messerschmitt_Me_323

However, too slow and an easy target.

But still, one of the first widebodied transports.

PS wikipedia mentions JATO as in Jet Assisted Take Off. Which in incorrect. It was a rocket assisted plane. As most in those days. Jets simply hadn´t the punch jet to make a difference. Wasn´t for nothing that in those days even jet powered aircraft needed some help now and then from rockets to take off.

But still wikipedia is kinda ok as a reference.

Movie of Gigant:

http://video.google.fr/videoplay?docid=2839532051306778677

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VEmn4WoYggY

Funny thing is that the Italian version of Wikipedia got it right and mentions RATO instead of JATO:

http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Messerschmitt_Me_323

Here another page with a nice pic of one the first engined versions, still only 4 engines. Later they put on 6, but still it was to heavy fully loaded to make a good take off, so they slemmed two rockets on it to really take off:

http://avia.russian.ee/air/germany/me-323.html

6 engined:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6e639Ec9lsQ

4 engined and 6 engined:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oIN6JCy02j8&mode=related&search=

I remember seeing a movie on http://www.movietone.com featering a gun-camera showing an attack on a ME-323 making a dash for the North African coast towards Rommels armies.

Have fun looking for it because it is not catagorised, so search for dates in a general way adn you may stunmble upon it… with loads of other interesting stuff.

oh… the ME-323 lost…

Very timely for Veterans Day in the U.S.!

While searching I came upon this report of an attack on the airport “Schiphol”, close to the village Amstelveen. It is the only recollection my stepdad has of WO-II because some bombs went wide or short and he was knocked over in his chair of the blast. (http://www.b-26mhs.org/content/view/180/119/)

Funny how my “dad´s” always got in the way of bombs… my bio-dad grew up in Oosterbeek (you know near Arnhem were all the bloodshed took place during Market Garden). He was with his dad and mom and his fake jewish “sister” who was in hiding with them( that´s another story of fate, luck and guts) in the shelter and suddenly a big boom and gone was the garden and most of the front of the house. We made jokes about that because my grand dad was a captain with “De Gele Rijders” (horse towed artillery in those days) and he bombed the hell out of a church because a German was there spotting for their artillery in during the German invasion in may 1940. He got a knighthood out of that stint btw. Here is picture of my granddad´s handywork on a church: http://www.grebbeberg.nl/bibliotheek/foto/foto.php?foto_id=2875

@ByTheSeas

ehmmmm…. the Mosquito was a English plane.

but what the hell veterans are veterans

;))

Fascinating stuff, Alan. Thank you.

I seem to remember hearing somewhere that the Japanese made use of wooden aircraft during WWII… possibly because Allied blockades made other building materials so scarce.

Has anyone else heard of this?

Re: JATO, until the spread of jet engines as we think of them today, rocket engines were frequently referred to as jets, so the acronym JATO for rocket assisted take-off is correct for the time period, even if it should be RATO to us. Additionally, that is where the Jet Propulsion Laboratory got its name, it was started as a rocket lab back in the Thirties, IIRC.

Re: Stealthiness, for the Mosquito it was important to avoid detection by ground radar, not just for bombing but for photo-reconnaissance as well. After all, if the enemy knows you are looking, they can take steps to hide what they are doing, but if they don’t know you are there, they may show you something they’d rather have kept under wraps.

I wonder why the Nazis never developed this type of plane in retaliation? From the quote it seemed as though there wouldn’t have been any confusions as to what these new planes were made of. Also, did America take any part in making planes like these? Or was it simply a matter of transportation across the humid ocean? Did the weather over in Europe ever affect the planes? I’m sure more questions will come soon.quote]

———————————————-

The Germans had trouble getting to that Ecuadoran Balsa Wood (or any other Balsa wood). The Japanese did use similar materials for some aircraft, IIRC, and I think Japan even tried to make an imitation Mosquito, but didn’t have sufficently powerful engines to pull it off. -Tha’s just from memory though, so don’t take it to the bank.

Just because that Mosquito was made of wood does not necessary mean that it would not show up on radar. If it were that simple don’t you think that every country would have a stealth bomber? We could go back to wood and canvas bi plains and make radar obsolete. Radar is capable of picking up a flock of birds it is certainly capable of picking up a painted wooden aircraft. Sheath Tec relies on special coatings and shape to “fool” radar. My guess would be that the fact that the Mosquito was made from wood would not affect it radar signature as much as it shape and paint job.

@Misfit

The Germans did make a copy in retaliation (they even called their own plane the Mosquito I believe), but it was a failure because German glue was of poor quality. This is the same reason the He-162 jet fighter was having trouble, because the wooden wings it had would fall off in violent maneuvering (that should be another topic, the He-162 Salamander! A metal fighter with wooden wings; plus, it actually did shoot down a single Spitfire at the end of the war. Go History Channel!)

The Mosquito was prominently mentioned in a recent show on PBS — Warplane, episode 2, I presume. The elliptical shape of its wing was noted, as well as the value of the wing’s thicker cross section than was considered feasible at the time. The program highlighted the plane’s use in guiding bombers more accurately (Mosquito-Oboe).

laughaminute said: “No, I don’t believe it was. But maybe if it was the windows wouldn’t have had a tendency to explode. :) It’s strange to think how the world of civil aviation might be so different now if it wasn’t for that small design flaw.”

What am I talking about? I always get the two confused.

I meant to ask whether the de Havilliland Swallow was built of wood. The first British plane and first jet plane to break the sound barrier. (The bell X-1 was rocket powered).

James said: “Just because that Mosquito was made of wood does not necessary mean that it would not show up on radar. If it were that simple don’t you think that every country would have a stealth bomber? We could go back to wood and canvas bi plains and make radar obsolete. Radar is capable of picking up a flock of birds it is certainly capable of picking up a painted wooden aircraft. Sheath Tec relies on special coatings and shape to “fool” radar. My guess would be that the fact that the Mosquito was made from wood would not affect it radar signature as much as it shape and paint job.”

Well, I would venture that radar technology has advanced a good bit since WW2. Radar is a form of radio waves mostly in the microwave part of the spectrum. It certainly returns a lot more strongly from metal than it does from wood or other organic materials. Radar also needs a flat, right angled surface to bounce off of, which explains the B-2 and F-22s’ curviness. Such curviness relates to the radar cross section, a measure of the detectability of the object you are broadcasting radar waves toward. You can reduce radar cross section by eliminating as much as possible the flat right angles and by using materials that absorb radar energy. So you are partially correct that wood alone does not stealthiness make, but only partially.

As for why no wooden warbirds today, metal is more durable, capable of greater stresses and is more consistent than wood with its knots, grains and whatnot. Wood is also a lot bulkier for the structure required.

As for the US not making wooden aircraft, there has always been a strong Not Invented Here bias in the military-industrial complex, not to mention the tremendous amounts of wood going to make Higgins boats, the Spruce Goose, and all the various structures required by the war. Not to mention that if the US had sufficient metal to develop and deploy Quonset huts all over the world, they most assuredly had the metal to make whatever aircraft they needed, even if the performance did not match the Mosquito. In addition, I would bet one gets better economies of scale working with metal than with wood, which was very important to winning the war the way America fought it.

Xiphias said: “What am I talking about? I always get the two confused.

I meant to ask whether the de Havilliland Swallow was built of wood. The first British plane and first jet plane to break the sound barrier. (The bell X-1 was rocket powered).”

Can’t answer that one, I wouldn’t even like to guess, although it did share a lot of design characteristics of the early DeHavilland jets, s0 maybe…

I’ve uploaded a few pictures that I took at the DeHavilland museum a while back if anyone’s interested.

Prototype Mosquito, Sea Venom wood and metal jet fighter and the cockpit of the Comet, the first Jet airliner:

http://img465.imageshack.us/img465/4687/dscf0520rp5.jpg

http://img364.imageshack.us/img364/9765/dscf0563ln4.jpg

http://img525.imageshack.us/img525/3249/dscf0594np2.jpg

First of all, I never said it was stealthy in the sense that it doesn’t show up on radar, it is stealthy in the sense that, for its size it has a smaller radar signiture then other planes of its size. In fact, no current know (public that is) plane is truely invisable to radar. More importantly, today’s radar systems are amazingly better then those of WW2. Many counties (Russia messed around A LOT with stealth technology, I’ll get to that later) claim to have many anti-stealth systems. Some are as simple as making the radar sender and recievers in a different places, so when the radar signal bounces away from the sender, a recvier somewhere else can still pick it up, to the extreme in which you use highly directive sound waves, Russia I believe CLAIMS to have that. The most “invisible” stealth type is probably plasma stealth. Feel free to look it up, but in short it absorbes the micro/radio wave by having thier energy create a plasma around the plane, it would basically be a aurora borealis arouund the plane. Also, you might not find much, but look up the U.S.S.R.’s “Ajax Project”. It was an attempt to make a hyper-sonic craft by means of ionizing the air on the leading edges of the plane. I need to go so just go here:

http://www.aeronautics.ru/plasmamain.htm

Wouldn’t a plasma field make it show up horribly on an Infrared view?

Yeah, and visible spectrum as well. Remeber, we’re talking about ionized gases, so cut-and-paste an aurora borealis over the plane, of course the Russians tested it more with achieving hyper-sonic flight (mach 5+). If your radar systems can’t see it but your optical and infrared can, it doesn’t matter when you’re target is traveling at mach 5+, again, the article I referenced to can explain it better.

DI! No more from this girl, I don’t know a thing about mechanics. Am gonna go find a biologocal topic to read. :) xxxoooLOL.

I would say that plasma coated aircraft would be advantageous to certain situations. Some armies dont have heat seeking missles, only radar. In those situations they would be invisible to those weapons. Sort of a rock paper scisors effect would take place. AA guns would be able to shoot at it though, so even if radar guided missles couldnt find it, a well aimed AA group could pick it off it it flew low enough. At the speed we are talking about (and likely altitude) wouldnt radar guided missles be its only enemy? Would sidewinders (heat guided) be able to catch it, or get close enough to use it?

Bewildered said: “Hi All!! I just registered because i love this site and find the articles damn interesting – this article included. But the real reason i registered is to say that i think there should be an article written about the attempts to be the first to post a reply… how old are you? Why do you do this? What dives your little brain to think it’s cool to post a first response on a website?!?! Grow up and concentrate on writing better comments than this one!!!”

Welcome aboard Bewildered – not that I post all that often myself, and hence hardly think I’m in any sort of position to welcome you aboard – welcome nonetheless.

As for first post – it is one of those things that has [dare I say it] evolved to become rather ironically amusing – in much the same vien as Shandooga has become ironically amusing.

These things aside it is still the most intelligent and amusing comments section of any website I frequent – and for all this I say thanks to everyone – group hug…c’mon Shandooga we all love you too. (thanks for taking it offline, I’m guessing you don’t use that email address for much? Golden rule: never post your email address anywhere on the web)

Keep it up one and all…

It is a beautiful aircraft. There is a restored one in the Aviation Museum in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. The Brits did not build too many nice looking aircraft, some of the others…in my humble opinion are the Spitfire, Lancaster Bomber and the Avro Vulcan.

I don’t really mind the first thing. Things like those make these posts amusing, and so do tangents.

Very interesting. One of the best articles here. Well anyways, I didn’t know wooden airplanes where used for war. And about radars having to have to have right angles, don’t stealth fighters have no right angles. So how are they detected? And exactly how do radars work.

sulkykid said: “Funny!

Of course it did. There were evolutionary predecessors to the Wright brothers as well as successors.

Well, you could not build a large suspension bridge from natural fibers. Balsa is a remarkable material. It is (I believe) the strongest wood when weight is considered. It is renewable and amazingly fast growing.”

The natives in South America in Peru or Bolivia I believe have been using suspension bridges constructed from braided vines for hundreds of years. They are capable of holding a pack animal. Normally they construct two side by side in case one breaks their not stranded. They have to be rebuild it every year. There is a National Geographic article on it out there somewhere. And by the way the Japanese’s Zero fighter was made of plywood also.

I never knew about these aircraft, and I thought that I knew World War II fairly well. Great article, and thanks for furthering my education!

Checking back in.

Over two years since I first read this article? Astounding.

I wasn’t going to post, but I cannot resist this one.

Three years have passed already? I suspect the next twenty – if I live that long – will be gone in the blink of an eye.